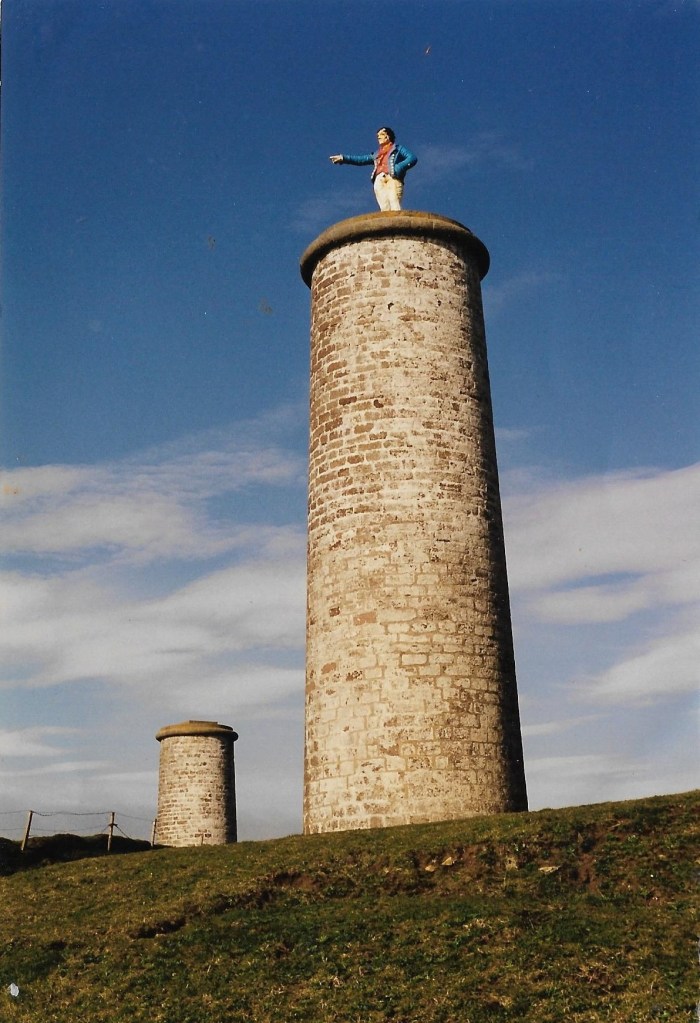

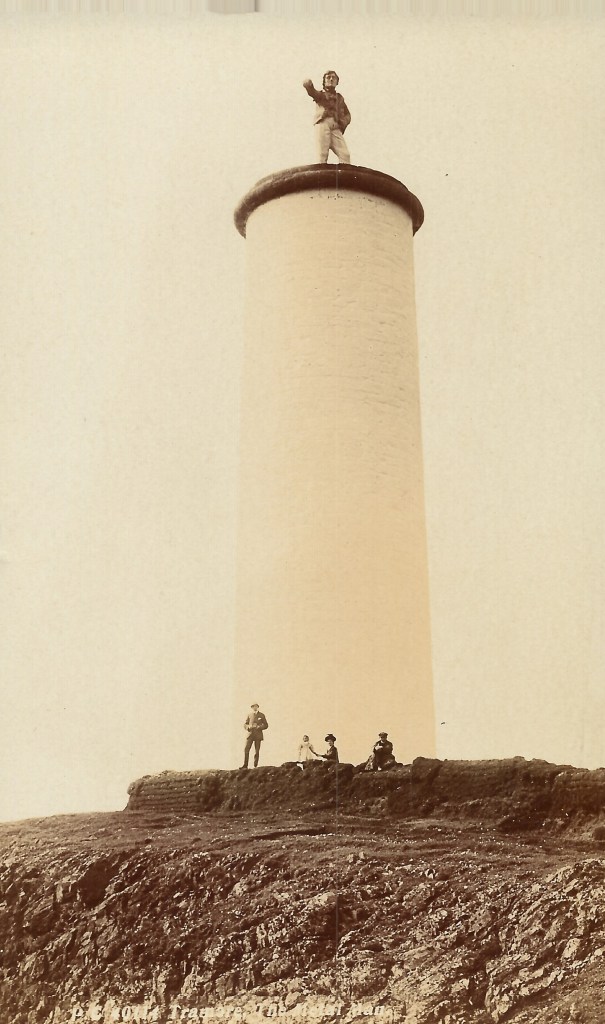

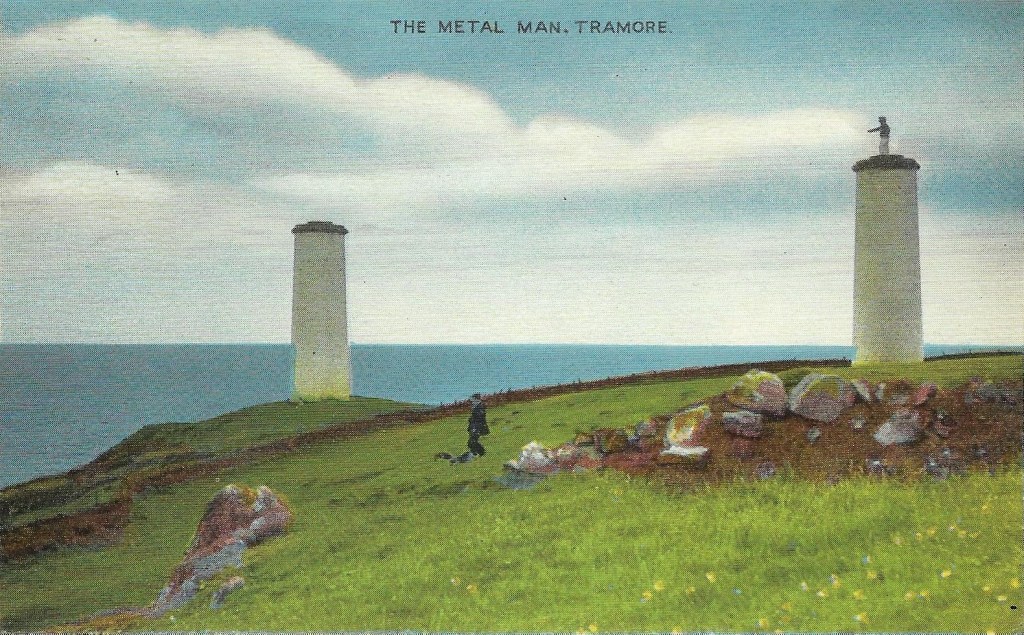

Since 1824, the towering cliffs at the entrance to Tramore Bay have been overseen by five imposing beacon towers—three situated on Great Newtown Head and two identical ones on Brownstown Head, standing tall against the backdrop of the rugged coastline. Perched on the central tower of the former is the iron statue of a sailor known as The Metal Man, a symbol of vigilance that gazes out over the treacherous waters, serving as a warning to passing vessels to avoid the perilous coast.1

The insurance company, Lloyd’s of London, is often credited with commissioning and financing the construction of these towers, as well as erecting the statue, as a response to the tragic loss of life resulting from the wreck of the Sea Horse in the bay in January 1816, when around three hundred and fifty people died. However, this commonly accepted narrative fails to withstand any significant historical scrutiny, as there is no evidence of Lloyd’s involvement in such matters; the company was simply not in the business of erecting beacon towers. It is crucial to understand the alarming frequency of deaths due to shipwrecks during this era. Estimates suggest that approximately 2,000 wrecks occurred globally each year between 1793 and 1815, highlighting the dire need for improved navigation aids. Sir G J Dalyell, writing from England in 1812, asserted that ‘perhaps not less than five thousand natives of these islands yearly perish at sea,’ underlining the severity of the situation that authorities desperately sought to address.2 In addition, the British armed forces incurred casualties exceeding 300,000 during the Napoleonic Wars from 1803 to 1815, illustrating the broader context of loss and tragedy that permeated society at the time. The loss of a few hundred soldiers and some low-ranking officers on the Sea Horse was described as a ‘Dreadful Calamity’ in the newspapers, yet these tragedies quickly faded from public memory, overshadowed by larger military causalities. The notion that Lloyd’s shareholders would be motivated to build the Tramore towers out of humanitarian concern does not align with the economic conditions of the early nineteenth century, a period marked more by fiscal prudence than idealistic philanthropy.

Planning and Construction

The following is a comprehensive account of the events that led to the construction of Tramore’s beacon towers and placing of the Metal Man, detailing the motivations, decisions, and efforts that ultimately resulted in these maritime safety structures. On 26 May 1818 a consortium of merchants from Waterford formally presented a petition to the Corporation for Preserving and Improving the Port of Dublin through the Waterford Ballast Office, in which they detailed the alarming frequency of fatal and destructive maritime accidents that had transpired in Tramore Bay. In light of these incidents, they proposed the establishment of navigational aids, specifically buoys and perches, to delineate the small channel of Rineshark Harbour as a potential refuge for vessels seeking shelter. While not specifically mentioned in the surviving correspondence, it is highly likely that the ship owner Richard Pope, owner of The Albion wrecked in Tramore Bay in 1811, was one of the merchants involved, as he frequently corresponded with both the corporation and the Chief Secretary’s Office at this time in relation to Waterford’s maritime trade.

The corporation may appear to be an atypical organisation with which to place such a request and probably warrants some explanation. Established by an Act of Parliament in 1786, its initial function was limited to overseeing the Port of Dublin until 1810, at which point its responsibilities expanded to encompass the management of lighthouses and beacon towers along the entirety of the Irish coastline. More commonly recognised as the Ballast Board , in early July the organization engaged Leyland Crosthwaite and George Halpin, an esteemed civil engineer and lighthouse commissioner, to assess the specific location. Their investigation concluded that marking the entrance to Rineshark would present significant hazards, as a treacherous bar of rocks obstructs the entrance at a depth sufficient to prevent vessels of even moderate size from accessing the harbour. They determined that the most prudent course of action would be to delineate the bay’s headlands by constructing three towers on Great Newton Head and two on Brownstown Head. Having finalised their survey by September, Halpin conveyed this decision to the board, which resolved to notify its superiors- the Elder Brethren of Trinity House at Tower Hill in the City of London.3

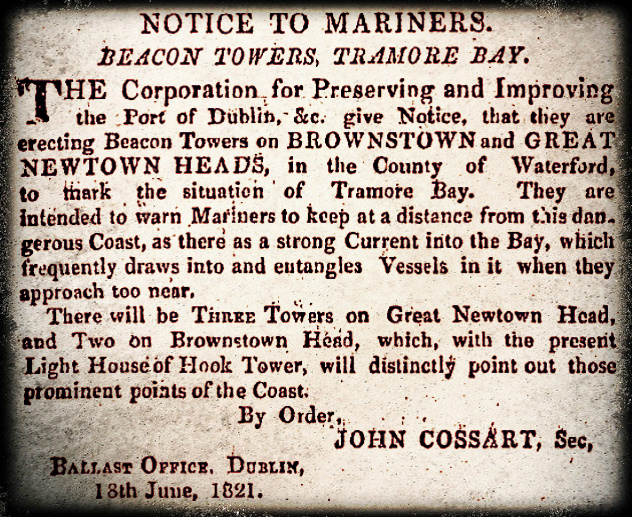

The decision of the board was likely influenced by the 18th-century charts of Waterford Harbour and Tramore Bay, initially created by William Doyle in 1737-38, which recommended the installation of a sea mark on Newtown Head to clearly differentiate Tramore Bay from Waterford Harbour. Neither Doyle’s chart nor the subsequent editions, those by Robert Sayers in 1787 and Laurie and Whittle in 1794, proposed a similar marking for Brownstown Head; thus, this advancement can be attributed to George Halpin himself. Consequently, on 14 November, John Cossart, the secretary of the Ballast Office, composed a letter to the brethren detailing these developments.

I am instructed to communicate to you for the information of the Elder Brethren of the Trinity House that a representation having been made by the merchants of Waterford that many fatal and destructive shipwrecks had occurred in Tramore Bay, and suggesting to the Corporation that it might be eligible to mark out a small channel called Rhineshark Harbour by buoys and perches as a place that might afford some shelter. The corporation have had the spot alluded to carefully examined and the result has been that they consider any mark that would lead mariners to seek for shelter there, would in most cases prove disastrous as a bar of sharp rocks runs completely across the small entrance which at low water is not covered more than one to one and an half feet and of course even at the height of the highest tides scarcely affords sufficient depth for a loaded vessel of moderate burthen to get over. The corporation therefore consider the most eligible precaution that can be taken will be to mark the headlands of the bay so as to make the situation of the bay easily ascertained and warn vessels to keep as far out as possible as there is an inland current which draws them into the bay when within its influence this will also prevent Tramore Bay being mistaken for Waterford Harbour which has been the case. They therefore recommend building three small towers on Great Newton Head and two on Brownstown Head, which with the one at Hook will completely distinguish the different headlands and bays and tend to render the navigation of that coast less dangerous.4

The letter was accompanied by detailed charts illustrating the perils of the bay and technical drawings of the proposed towers. In response, James Court, secretary to the Corporation of Trinity House, issued a letter dated 4 December 1818:

I have received your letter of the 14th ult accompanying a chart of Tramore Bay and of the entrance of Waterford harbour and stating the plan proposed to be adopted for marking the headlands of that bay by three small towers on Great Newtown head and two on Brownstown Head as the most eligible precaution that can be taken for preventing the frequent shipwrecks that occur in Tramore Bay in preference to marking out the small channel call’d Rhineshark Harbour as suggested by the merchants of Waterford. And the same having been taken into consideration by the Elder Brethren of this corporation to acquaint you for the information of the Commissioners of Irish Lights that the Elder brethren entirely concur with them in the opinion that the marking of the headlands of Tramore Bay by towers as before mentioned is the most eligible precaution that can be adopted under the local circumstances of the place, for the prevention of shipwrecks in Tramore Bay.5

Having reached a formal agreement, John Cossart subsequently dispatched a letter to Charles Grant, the Chief Secretary of Ireland, on 22 January 1819, addressed to the Lord Lieutenant for his consideration:

I have the honour to enclose by directions of the Corporation for Preserving and Improving the Port of Dublin & C., a copy of that part of a letter from them to the Elder Brethren of the Trinity House London suggesting the expediency of erecting three small towers on Great Newtown Head and two on Brownstown Head at the entrance of the Harbour of Waterford as also a copy of part of a letter from that corporation dated London 4th December 1818 approving of the same, both of which you will please to submit for the consideration of His Excellency the Lord Lieutenant.6

Having been made familiar with the case, the Lord Lieutenant then authorised the construction of the towers by early February 1820, and subsequently the board ordered George Halpin to inspect the sites at the headlands. It was not until 29 April, after concluding his assessment, that he reported back to the board. The land at Brownstown Head was owned by Lord Fortescue and leased to Mr. A. Alcock, while Great Newtown Head was part of Mr. J. Power’s estate, who purportedly expressed a willingness to provide the sites under reasonable terms. In addition, the Board communicated with the landowners to inform them of the project and to inquire about the terms for acquiring the necessary land.

Mr Power wholeheartedly consented to the construction of the towers, while deferring the determination of damages to the judgment of two appointed judges. Subsequently, the Waterford Chamber of Commerce was tasked with appointing individuals to oversee the arbitration process concerning damages to Mr. Power’s estate. On 1 July 1819, the Waterford Chamber communicated a letter to the Board, expressing Mr. Power’s concerns regarding unauthorised access and trespass, along with his willingness to lease a minimum of three acres at a rate of £3 per acre, over a period of 20 years. Mr. Power also raised objections concerning the selection of the two judges, asserting that access to Newtown Head should remain open solely during the projected one-year construction phase, and stipulating that in the event of any trespassing by the contractor or his employees, the contractor would be liable for compensation. The Board accepted Mr. Power’s conditions and directed the Law Agent, Mr. Rooke, to execute the necessary measures for the acquisition. It was not until February 1821 that Rooke informed the board that Mr Power had consented to transfer the necessary interests in Great Newtown Head for the sum of £60.7

In August 1820, Lord Fortescue despatched Robert Ballment, his land surveyor, then residing in Devon to Waterford, to inspect the intended site for the towers on Brownstown Head. Ballment was informed by Mr Brownigg at the Ballast Office that the two towers were to be built to a height of about 61 feet each and that no one was to reside in or near them after they were finished. The only access to them was to be by way of a footpath for maintenance from time to time. Ballment then informed Mr Rooke that Earl Fortescue would be satisfied with two guineas per annum for the standing of the towers with a right of a path to them for the purpose of seeing that they were in repair. Under such terms, he believed that Earl Fortescue would grant a term of ninety-nine years, although he would expect compensation for the stone taken from his cliffs for the building of the towers, about £10 a tower.8 Ballment then wrote to Lord Fortescue in a letter dated 5 October 1820 and advised that he could not see how his Lordship ‘could sustain the least convenience as the towers when built will in all probability stand for a hundred years without any repair, as they are to be built in such substantial manner and all with hewn stone and to be capped with granite of very large dimension.’ Evidently, Lord Fortescue agreed to the terms as Mr Rooke was instructed to negotiate with the sitting tenants.9 However, these negotiations proved to be difficult. The land on Brownstown needed to access and build the towers was located on two farms, and it was not until 27 March 1821, that the occupier of the first of them, Robert Kirwan, leased 60 perches of land for a short period, to the board at the cost of £5 13s. 9d..’ While the negotiations with the Power brothers the occupiers of the second farm were even more protracted. Consequently, it was not until 25 September 1822, that the brothers leased three roods of their land for the extraordinary sum of £50 11s.10 Rooke regarded this as a fraud upon the board. ‘By means of these two leases the Corporation was finally in possession of all the land necessary to build the towers at Brownstown.’11

While the land negotiations were ongoing, the board’s plans for the construction of the towers continued to advance. The specification for the work, dated 21 July 1820, was issued from the Ballast Office in Dublin. It stated that the walls were to be entirely composed of ashler, roughly hammered, and with square backing. Each course was mandated to be laid alternately with headers and stretchers. The entire structure was to be laid flush in mortar and thoroughly grouted at each course. The mortar composition required one part well-burnt lime and three parts clean freshwater river sand. The contractor was responsible for supplying the stone, lime, sand, scaffolding, wheelbarrows, planks, and all necessary implements for the successful completion of the works. The upper three courses of each tower were to be constructed of granite or sound limestone, properly wrought, closely jointed, and fully bedded, as detailed in the plan, elevation, and section. Each tower was to reach a height of sixty-one feet above the surface, with foundations firmly laid on the rock, which was presumed to be near the surface; the contractor was to verify this. The entire work had to be completed to the satisfaction of the engineer appointed by the corporation. Any ambiguity regarding the interpretation of the specification was to be clarified by the engineer. In the event of unsatisfactory work, the corporation retained the authority to dissolve the contract and complete the work under the supervision of the engineer or another contractor, with the original contractor and his sureties liable for any additional expenses incurred. The completed work was to be delivered to the corporation within twelve months from the contract date. The contractor was required to propose a specific sum for the completion of each tower and to identify two sureties, jointly liable for the sum of £1000, for the proper execution of the works within the stipulated timeframe.12

In August 1820, the following advertisement for tenders to construct the towers was inserted in numerous Irish newspapers.13 Proposals detailing the methods and estimated costs were to reach the secretary before 1 September, limiting all interested parties to less than a month to prepare their submissions:

In total, nine proposals were submitted by contractors, with bids widely varying from £675 to £1950 per tower. After a thorough review process, Edward Saunders was awarded the contract on 28 September, as he presented the lowest tender, which not only met the budgetary requirements but also promised a quality of work that was in line with the board’s expectation. Prepared to move forward with the project, the board subsequently had the following announcement published in The Freeman’s Journal notifying the maritime community of its intentions:

Recent discussions have hinted that the towers and Hook Head serve as some sort of intricate countdown system; however, this notion strikes me as quite dubious and seems to suggest a troubling incompetence among mariners. It is important to clarify that no such system was referenced in the planning of the towers beyond the description in this published notice. Nor are such instructions given in subsequent nineteenth-century navigational guides.

While the negotiations for the properties at Brownstown Head were still ongoing, work proceeded on the towers at Newtown Head and by May 1822 at least one of the towers had been built to a height exceeding thirty-seven feet. This information comes to us by way of a local newspaper report of a terrible accident that occurred when two men working on one of the towers fell from a height and were both horrifically injured:

A shocking accident occurred on Saturday last, at Newtown head, at the western extremity of Tramore Bay. Two of the masons employed at the Towers erecting there were in the act of ascending to the top of one of the towers, by means of the apparatus used in raising up stones. &c. when the old rope by which they were suspended and which had been badly spliced, gave way at the spliced part, by which the unfortunate men were precipitated to the ground from a height of thirty-seven feet, and so severely injured that their recovery is extremely doubtful. One of them, named Byrne, a native of Wexford, was brought to the Leper Hospital, in this City, on Sunday evening, in a most pitiable state, having suffered a fracture of the spine, besides various other fractures and contusions. The other, named Flaherty, remains in Tramore, of which he is an inhabitant, in a state almost equally miserable. Both we understand, have large families dependent on them for support, who we have no doubt will experience the liberality of the contractors and the public.14

A stipulation for the works specified that the contractor would assume sole responsibility for any accidents that occurred during the execution of the work. Nonetheless, over five months later, on 7 November, The Waterford Chronicle published an urgent appeal for charity from the public, as the authorities had not provided any financial assistance to support the bereaved families:

Case of Great Distress:-The benevolent and charitable disposition of the citizens of Waterford is so universally known, that we feel it only necessary to state a case of real distress to the public to bring that disposition into action:- Our readers may recollect that, some months since, two men employed at the Beacon Towers erecting at Newtown Head, near Tramore, were precipitated from a height of 40 feet to the ground, by the breaking of a rope of the windlass by which they were being conveyed to the top of the works; one of those unfortunate persons, John Byrne, an industrious mason, was so injured by the fall, that he was taken to the Leper Hospital, where he lingered in the greatest torture, without any hope of recovery, though attended by Doctors Burkitt and Mackesy, and expired a few days ago, leaving a widow and three small children in misery and want, he being their principal support. We regret to state, that an application which was made by the Rev. Mr. Cooke, Rector of the Parish, to the Board of Works, and to the chamber of Commerce, for relief for the unhappy sufferers, has not been attended with success, inasmuch as the funds of those respective bodies cannot be appropriated to such purposes. Under these circumstances, the case of the widow and three hapless children is laid before the public, in the hope that some relief may be obtained. The smallest donation will be received by Doctors Burkitt and Mackesy, the Rev. John Cooke, Westland Tramore, and at the Newspaper Offices, Waterford.15

The annual expenditure of the Ballast Board concerning the planning and construction of Tramore’s beacon towers is documented in the annual reports of the Commissioners for Auditing Public Accounts in Ireland for the years 1819-1824. The aggregate expenditure during this six-year span totalled slightly over £4043.16 A substantial portion of this expenditure was allocated to the builder Edward Saunders, who received an advance of £1000 for the fiscal year 1821-1822 and an additional £2400 for the subsequent year, culminating in a total of £3400, an amount that slightly exceeded his initial estimate of £675 per tower. Upon fulfilling the obligations outlined in his contract, the builder would rightfully have had his bond of security returned. Other expenses included those of Mr W. D. Rooke who was advanced £300 to cover legal costs.

The following notice, dated 10 January 1823, was apparently published in the Freeman’s Journal: Notice to Mariners. Beacon Towers, Tramore Bay. The Corporation for Preserving and Improving the Port of Dublin has erected Beacon Towers on Brownstown and Great Newtown Heads in the County of Waterford to delineate the location of Tramore Bay and hereby notifies Mariners.17 In April George Halpin reported that the five Beacon Towers were nearing completion. However, it was not until nearly a year later in March 1824 that he reported that, ‘the two towers on Brownstown were constructed, ensuring that mariners would not confuse this headland with Hook Point.’ Halpin further noted, ‘On Great Newtown Head, three towers were erected, with a twelve-foot sailor atop the middle tower, his right arm extended; these three towers are essential for preventing mariners from misidentifying Great Newtown Head for Brownstown Head.’ The historian R.H. Ryland, in his book published in 1824 stated that ‘beacon towers have been recently erected at the earnest solicitation of the harbour commissioners, who had much opposition to contend against’.18 However, he doesn’t mention the Metal Man statue and it may not have been erected at the time he was writing.

The Metal Man

The statue of the Metal Man was designed by Thomas Kirk, a sculptor and architect born in Cork, who initially presented a sketch at the Hibernian Society of Artists in Dublin in 1815.19 His most renowned work is arguably the statue of Admiral Nelson on his column on O’Connell Street, that was blown up in 1966. However, historical records from the Ballast Board indicate that George Halpin was the first to propose the idea of placing a statue of a sailor atop a beacon at Black Rock, County Sligo in December 1816.20 Subsequently, Kirk crafted a small model that was exhibited in London in 1817, titled ‘A British Tar, a sketch designed for a colossal statue, 12 ft. high, now executing for the Ballast Office Co. to stand on a dangerous rock in the sea near the harbour of Sligo as a beacon.’21 The term ‘Tar’ is derived from Jack Tar, a common English term that was originally used to refer to seamen of the Merchant or Royal Navy, particularly during the nineteenth century.

By 1819, the board resolved to position cast metal figures atop four beacon towers along the coast: one for the noted Blackrock in Sligo, one on each of the headlands at Tramore, and a fourth designated for either Beeves Rock or Scarlett’s Rock in the River Shannon. In May, Kirk’s tender of £75 was accepted for creating a model of the statue. Subsequently, in November, John Clark’s tender to cast the statues at £80 per figure was approved. According to J. P. Entract, the ‘statues were cast at a cost of 23 shillings per hundredweight, a price deemed excessive at that time.’22 Judging by these figures each statue weighed just under three and a half tonnes. The following section provides a detailed description of the statue from the Commissioners of Irish Lights:

The cast iron figure is twelve feet high and depicts a sailor of that period standing with his right arm extended, pointing out to sea away from danger, and his head is looking in the direction of the pointing arm. His trousers are white, jacket blue with yellow buttons, waistcoat red, hair and shores black and his face and hands pink.23

Accordingly, the first statue was dispatched to Sligo. A memorial from the Sligo Commissioners and Shipmasters, dated February 1821, requested the transformation of the Blackrock Beacon into a lighthouse and proposed that the Metal Man, currently stored in Sligo, be positioned upon a ten-foot high pedestal on Perch Rock to serve as a navigational aid for the anchorage at Oyster Island. The commissioners issued an advertisement in the newspapers on 7 January 1822, soliciting ‘plans, estimates, and proposals for the construction of a suitable pillar on Perch Rock, to be no less than ten feet above high water mark, upon which the ‘Metal Man’ presently residing on the new quay shall be affixed.’ February 11 was designated as the date for the appointment of the contractor.24 The statue was probably positioned a relatively short time after this date.

It was not until April 1823 that George Halpin reported the near completion of Tramore’s five Beacon Towers, with the exception of the two metal figures, thus confirming the intention to place a figure at each headland. Regrettably, the two statues designated for Tramore Bay went missing, and the Board’s minutes offer no account of their fate, nor did this incident attract any significant media attention. Consequently, the statue intended for the Shannon was redirected to Great Newtown Head. On 19 September 1823, the 12-foot metal statue was unloaded at Waterford, having arrived from Dublin, and was noted to have been ordered ‘to be positioned on one of the towers at Brownstown Head to direct vessels towards Waterford Harbour.’ However, this was later identified as a mistake by a journalist, whose error was soon rectified in the following edition:

A large cast iron statue of a man has been landed at Waterford, from Dublin and has been sent to be placed upon the middle tower of the three towers lately built at Newtown Head, the western part of Tramore bay, in this county, with the left hand akimbo, and the right extended out, as a warning to vessels to keep off from that dangerous shore. This is the statue that was stated erroneously, to be intended for Brownstown Head at the other side of the bay, and to direct toward Waterford Harbour.25

Unfortunately, this error has persisted and up to the present day there are those that still insist that the Metal Man points towards Waterford Harbour, rather than to the relative safety of the open seas.

Somewhat unusually, there seems to be a lack of any ceremony or documentation associated with the installation of the statue, as the writer has not found any references to the Metal Man being positioned until a poem was published in the Waterford Mail on 4 September 1824.26 This absence of formal recognition raises questions about the statue’s initial significance and the perceived extent of the towers intended purpose. It remains uncertain what impact they may have had on maritime safety. Less than two years following their completion, two vessels, the Flora and the Bolton, were wrecked at Tramore on 19 December 1825, marking a grim reminder of the dangers that still loomed at sea. The esteemed local historian Matthew Butler was of the opinion that ‘Whatever value these towers are to ships in daytime, their value at night must be negligible for they cannot be seen.’27

Furthermore, during inclement weather, when visibility was most critical, the towers would likely have been obscured by thick fog or heavy rain, which would have rendered them ineffective as navigational aids. The decision to forgo a lighthouse, an option that while more effective, would have been significantly more expensive to construct and maintain, hints at the economic considerations of the time. Although, the fear of its proximity to Hook Lighthouse leading to navigational confusion for mariners was probably the most likely factor in deciding against a light. What is certain is that the shipwrecks in Tramore Bay persisted through the age of sail and advanced into the age of steam and illustrated the ongoing struggle between maritime navigational progress and the perils of the sea.

The Tramore and Brownstown Beacons were probably first mapped in Samson Carter & Noblett St Leger’s Chart of Waterford Harbour published in 1835, at which time the responsibility for the maintenance of the towers was still entrusted to the Ballast Board, which ensured that the structures were regularly whitewashed. Throughout the years, various tradesmen executed the painting of the Metal Man and the towers. An intriguing technical drawing from the 1850’s exists, depicting the cradle employed for these works, which includes details such as galvanized bolts and MS angle plates, stored in the archives of the Commissioners of Irish Lights. This organization assumed responsibility for Irish maritime safety beyond Dublin port in 1867.

On 4 August 1894, a local newspaper published an article detailing an incident that occurred in relation to the increased naval reserve artillery practice during the previous week, which the writer amusingly attributed to the prospect of European developments in the Sino Japanese War influencing the reserves to show that they mean business should occasion arise:

During the past week, the boom of the big gun at the Doneraile was frequently heard. I cannot yet compliment the marksmen on their performances. A short time since a friend was strolling over the cliffs when he was startled by a loud ‘whirr,’ and almost in an instant masonry began to fall from one of the pillars at the Metal Man. It was struck by a cannon ball from the battery. I think that the artist that accomplished this feat should be superannuated without delay. As far as I am aware, the poor Metal Man never offended mortal.28

Regrettably, with no legal access to the Metal Man towers, the author has been unable to confirm whether one of the towers had indeed been struck by such ordnance. However, records indicate that two years earlier, a firing battery had been established at the cliff’s edge by the Board of Works, where the gun now positioned at the Doneraile had been located during the 1970s and 80s. This gun, thought to have been first deployed during this period, is probably either a 7” or 10” Rifled Muzzle Loader. The rifling of the barrel provided greater range and accuracy compared to the smoothbore guns of the past. The distance from the firing battery to the Metal Man, as the crow flies, was just under 2.5 km, which, while exceeding the range of the smaller gun, falls comfortably within the range of the larger one, suggesting that there may be some truth to the tale, although there may be a more likely source of the noise.

Two days before the story of the tower being hit by gunfire was reported, Michael Kirwan, the contractor who was for several years responsible for painting and lime washing the Metal Man towers fell to his death. It appears that he raised himself to the top of the tower by means of blocks and pulleys, but the support which sustained the pulley was not sufficiently firm in the ground and it gave away. He fell 60 feet and was killed. He left a wife and large family behind to mourn his death. The body was removed to the assembly rooms and an inquest was to be held the following day.29 On 31 May, the following year, Mr H. E. Benner of Spring Hill House penned a letter to The Waterford News stating that a small fund had been set up from the subscribers to the newspaper to raise money in aid of his widow and seven young children. The fund was to be used to give Kirwan a decent burial and to assist his family to live through the severe winter in comparative comfort. Over £17 was raised and was used for the funeral expenses, a sum cash for Mrs. Kirwan, a weekly allowance for 84 weeks with a coal allowance, with the leftover balance of just over £2 lodged into the Post Office Saving Bank in Tramore in her name.30

In Rhyme and Legend

There have been several rhymes and poems written about the Metal Man over the years, with the most commonly known being his warning cry, ‘Mariners all, keep out from me. For I’m the rock of misery‘, the earliest known rendition of which was published in September 1896.31 This haunting refrain has captivated the imaginations of sailors and landlubbers alike. Another version from 1900 reads: Keep off, keep off from me. For I’m the rock of misery. Each iteration carries a sombre tone, emphasizing the dire consequences of ignoring the Metal Man’s warning. While Edmund Downey’s version in ‘A Guide to Tramore‘, published in 1919, which seems to be the most popular modern rendition reads: Keep off, good ship, keep off from me; for I’m the rock of misery. This adaptation lends a casual charm while maintaining the original’s eerie warning. Whereas in 1928, Bertram Poole, who knew a thing or two about local folklore, recited: Keep off, keep off, keep off from me, For I’m the rock of misery. The repetitive structure in this version heightens the sense of urgency and desperation, resonating with those who have navigated the perilous waters near Tramore. For what it’s worth, I’m for sticking with the original version, as it encapsulates the raw emotion and traditional warnings that have echoed through generations of seafarers, reminding us that the Metal Man remains a symbol of both danger and folklore that deserves to be remembered and respected.

There is a legend associated with the Metal Man that claims that any unmarried woman who manages to hop around his tower three times will find herself married to a suitable husband within the year. This popular local tradition appears to have come to light in the early years of the twentieth century, as it was previously absent from newspaper reports and guidebooks. It first appears to be illuded to in a piece on the Metal Man that was published in the Waterford Mirror in June 1903, when ‘His Eminence’ as he was somewhat unusually referred to, was credited with ‘so many chivalrous propensities in the locality, that there were few feats of romance beyond his reach of accomplishment’.32 A more complete version of the myth comes in Victor O’Donovan Power’s novelette ‘The Barrington Jewels’ which was published in January 1904. In it one of the characters, ‘old Peggy Brophy’ while on a visit to Tramore many years previously was ‘recommended to go round and round the ‘Metal Man’ on her knees three times…as a remedy, or charm, for some complaint from which she suffered?’ 33

However, it is through Arthur Henri Poole’s postcards that the story became popular. Indeed, the oldest mention of the legend in its present form that the writer has come across is from an edition of the Kilkenny Moderator published in 1905 that reads: ‘A postcard before us bearing a pretty device has the following legend-“It is said that any unmarried ladies who succeed in hopping around this pillar three times will be married within the year’.34 Poole’s postcards can be traced back to 1902 at the earliest, the year when the British post office first permitted the use of postcards with a divided back, allowing messages and addresses to be written on one side while reserving the front solely for imagery. Power’s narrative may have been inspired by a Poole postcard, or alternatively, the captions on Poole’s postcards could have drawn influence from Power’s novelette. Furthermore, the legend in question may possess much deeper historical roots that have gone unnoticed by writers. Additionally, it might have originally been linked to a nearby location, evoked by another Poole postcard depicting the entrance to the Mermaid’s Cave, which presents an ‘old tradition that any unmarried persons who visit this cave will be married within a very short time.’

Nonetheless, in August 1908 a reporter from the Kilkenny Moderator witnessed several young ladies performing the rite:

On Sunday afternoon last a number of young women were seen amusing themselves around the great pillar on which stands the “Metal Man” on one of the boldest cliffs in the neighbourhood of Tramore. Several of these young women were hopping on one leg around the pillar, each trying to accomplish in this fashion three circuits of the pillar without stopping, the idea being that the young woman who succeeds is sure to be married within the year. As they proceed merrily and utter failure marks their efforts, the fun waxes furiously, but ends with a languishing sign and the exclamation, “Oh, I won’t be married this year”! 35

The myth seems to have greatly added to Tramore’s popularity. A 1911 edition of ‘The Literary Lounger’ featured a large image of one of Poole’s photographs of the Metal Man with a caption added describing the myth and stating that many lady visitors were attracted to Tramore to test the value of the legend.36

Arthur Poole’s son, Bertram, who was born in 1886, developed a profound interest in the folklore of Tramore. Moreover, his mother Elizabeth, whose maiden name was Moran, hailed from ‘Pier View’ on the Doneraile Walk. In July 1928, Poole published an article in the Cork Examiner detailing the Metal Man legend, and acknowledging the challenges in pinpointing the legend’s origins, noting its obscurity until his father’s company circulated a postcard of the tower featuring the legend inscribed below. Consequently, the tale gained widespread attention, drawing numerous visitors eager to attempt the challenge each summer. However, the endeavour proved significantly more difficult than anticipated, as the tower’s broad base and the surrounding sloped, stony terrain hindered efforts. Very few individuals succeeded in completing even a single circuit, much less the required three. Some resorted to leaning against the tower out of sight to break the spell, yet Poole said that ‘the Metal Man remained unconvinced’. Poole confidently stated that any woman possessing the requisite strength and determination to accomplish this task would similarly find success in securing a husband if she set her intentions toward that goal. In Poole’s opinion, while the authorities may not have achieved their original aims in constructing these pillars, they undeniably provided a source of amusement for many pleasure-seekers ever since.37

A Tourist Attraction

The Metal Man undoubtedly gained in popularity when the Coast Road was constructed in the 1870’s, allowing visitors to take a jarvey car from Tramore to Newtown Cove and then as the characters in Power’s novelette did:

Across the daisied fields, over the furzy banks, down to Newtown Cove, and up the zig-zag foot-way to the opposite cliff-top- then along the winding path by the dizzy verge of the cliffs, with the great blue-green billows thundering in upon the jagged rocks sixty feet below-the merry party proceeded, never pausing until they had reached the three great pillars…

Indeed, from this time on, it’s hard to find an article on Tramore as a tourist resort that doesn’t mention the statue, so great had its appeal become: ‘In Tramore you are not supposed to have seen anything unless you have feasted your eyes upon the sea beaten countenance of this much admired individual’.38

Up until 1930, all the towers underwent an annual whitewashing. However, between 1930 and 1957, the Brownstown towers were coated with tar, while the Great Newtown structures remained whitewashed. Notably, the capping stones of the Metal Man tower were painted black during this time. An article published in The Dublin Leader in 1945, described ‘Brownstown Head with its pair of black beacons‘ and pondered the difficulty of getting there, asking if one day the authorities would make ‘expeditions there a practicable proposition‘.39 Following on from the year 1957, when the brickwork required pointing, it was decided to halt the practice of painting all the towers, with the Metal Man figure being repainted every three to four years.40 But even this practice seems to have lapsed.

Early in 1972, the Tramore Tourist and Development Association formally requested the authorities to paint the towers, as their appearance had become quite dilapidated. This matter had been raised multiple times in recent years by both the association and the Munster Express; and despite the Metal Man being painted, the towers remained untouched. There was a growing sentiment that both the South Eastern Regional Tourism Organisation and Tramore Failte ought to assume greater responsibility for what was often referred to as ‘this special attraction of Tramore.’ A report from the meeting described the legend of single women hopping around the central tower, a tradition that had persisted for a few generations, and proposed that funding be secured to apply a coat of cement or tarmacadam around the base to enhance safety and improve the site’s appeal as a tourist destination.

At that time, the landowner was a farmer named Johnny Doyle, who was described as an amiable, no-nonsense type of character. The property had been in his family for a least four generations stretching back to his great grandfather Patrick Doyle who farmed the land during the hardship of The Famine. Nonetheless, he prohibited public access to his land in 1974, asserting that he could no longer permit visitors due to vandalism that posed a serious threat to his cattle. Vandals had dismantled a stile he had constructed at the cliff, destroyed his barbed wire fences, and trampled his crops during their visits. He cited a recent incident at Garrarus where several cattle plunged over a cliff, due to a broken fence. Additionally, he had to intervene to stop youths from playing hurling and football matches on his land. He further remarked that the tourist authority was welcome to purchase his property as a recreational amenity if they sought to provide access to the Metal Man, but he was no longer willing to permit tourists on his land, jeopardising the safety of his herd.41

In order to keep trespassers off his property, Doyle erected barbed wire fencing and padlocked the entrance gate on which he also hung no trespassing signs. He was said to have kept a constant watch on the site.42 Indeed, some Tramore people have childhood memories of him sitting on a ditch with a shotgun in hand during summer days, deterring would be trespassers.

Local tourist interests urged for a resolution, emphasising that thousands of frustrated visitors were being denied access to a location that had historically been open to them. Nonetheless, the council’s legal efforts to have the barbed wire removed and to restore public access to the area proved unsuccessful. While still open to selling the property, Doyle correctly asserted that the right of way from the public road to the Metal Man was exclusively granted to the Irish Lights Commission only.43 The state-supported development organization Tramore Failte Ltd subsequently sought to improve access to the area with the backing of Waterford County Council, which offered £10,000 to Mr. Doyle for the section of land where the Metal Man is situated. Considering the subdivision of his property detrimental to his agricultural operations, Doyle declined and proposed to sell the entire plot of land on that side of the road for £40,000, an offer that the council turned down. As a result, Mr. Doyle upheld his prohibition of access to the towers until his death in January 1981.44 Most of the 1980’s seem to have passed by without any renewed initiative for public access to the Metal Man site, nor any substantial maintenance of the statue and towers. This is unsurprising, given that Ireland was enduring a prolonged period of recession and stagnation during this decade.

In 1989, The commissioners for Irish lights were asked to improve the navigational markers at the entrance to Tramore Bay by Waterford Harbor Board. The chairman of the Waterford Harbor Commissioners Mr. Cummings said the situation was quite serious and several ships had gone into the bay only to make a hasty retreat after discovering their mistake. The Hook Light was often obscure in heavy rainstorms and the harbour commissioners felt that a new light or some other marker should be placed on Brownstown Head or Newtown Head to alert shipping. The beaching of the Gladonia there recently highlighted the need for more modern navigational aids.45 However, the Irish Lights Commission later released a statement asserting that the towers could no longer be regarded as effective navigational aids and held diminished importance for mariners. Advanced modern equipment had supplanted these once-familiar landmarks, which prompted the commissioners to install specialised navigational devices in the Hook Head Lighthouse, to ensure that mariners could accurately identify the entrance to Waterford Harbour. The entrance to Waterford had been further improved by the leading lights of Duncannon and Dunmore East. The commissioners noted that there was no justification for illuminating the Metal Man towers or the beacons at Brownstown Head. A newspaper report remarked, ‘Now that the Metal Man has entered retirement, he is to receive a new coat of paint from the Irish Lights Commission in acknowledgment of his century-and-a-half of service.‘ 46

Subsequently, the commissioners approached Waterford County Council with a proposal for them to take over the famous historical attraction , but this offer was declined due to financial constraints.47 In December, Tramore Town Commissioners convened a meeting to appeal to South East Tourism in an effort to preserve the iconic landmark, following the commissioners’ decision to cease operations on the grounds that it no longer served a practical function as a guide for shipping. Councillor Casey still contended that, aside from its significance as a tourist destination, it could still provide valuable guidance for fishing vessels and leisure cruisers.48

In August 1992, an anonymous letter was published in the Munster Express expressing the hope that the owner of the land at Newtown Head might consider donating a strip of land to facilitate public access to the attraction, as had been customary for families in the past. The letter also suggested that Bord Failte could enclose the cliff to create a scenic cliff-top walkway from Newtown Cove.49 The following year, a public meeting convened at Joe O’Shea’s hotel to address the restoration of the Metal Man witnessed disappointing attendance. At the meeting it was pointed out that while Irish Lights still had responsibility for the towers, they were slow to maintain them. Mr Casey, then Waterford County Council chairman and Tramore town commissioner stated that ‘as an old landmark which is part of Tramore’s heritage, it would be a pity if it were allowed to deteriorate and it should be painted.’ In the long term and given an improvement in the financial situation generally, he anticipated that the county council might be able to assume responsibility for the site and maintain it properly, as well as provide access to it.50

A decade later, in September 2003, the town council was still deliberating on the ownership, maintenance of and access to the Metal Man. Councilor O’Sullivan pleaded for the Metal Man to be given a lick of paint urgently because it had become a rusty embarrassment. The statue had been last painted in 1996. She added, ‘I really feel that we need to take ownership and decide what to do with it.’ Councilor Gavin told the meeting that it was his understanding that Irish Lights had fully handed ownership over to the co. council. The county council’s director of corporate affairs and housing, Mr Carey told councilors that discussions with the landowner in the area in relation to access were at a sensitive stage. Another councillor proposed that if ownership lay with the county council, they should register the monument’s trademark and logo, establishing a fee structure to finance maintenance.51 In fact, the councilors were misinformed and no such transfer of ownership had taken place at that time.

The potential for transferring ownership of the towers and facilitating public access has been raised multiple times in recent years. Notably, in 2012-13, when the short-lived Tramore Heritage Ltd company’s initiative to acquire ownership and significantly enhance access to the site was halted by some council members on the questionable basis that the Metal Man could under certain circumstances transition into private ownership.52 It was not until 23 October 2015, that ownership of the Tramore and Brownstown Beacons was officially transferred from Irish Lights to Waterford City and County Council. The ongoing situation of prohibited access to Tramore’s most significant historical landmark remains unresolved to this day, despite the bicentenary of the towers having come and gone.53

- The five structures on the headlands should be referred to as towers, as the commonly used term ‘pillars’ is inaccurate, the difference being that towers are self supporting, while pillars are load bearing. ↩︎

- Terrence Grocott, Shipwrecks of the Revolutionary & Napoleonic Eras, London 1987, page vii. ↩︎

- In 1566 Queen Elizabeth I’s Seamarks Act empowered Trinity House’ at their wills and pleasures, and at their costs, make, erect, and set up such, and so many beacons, marks, and signs for the sea… whereby the dangers may be avoided and escaped, and ships the better come into their ports without peril.’ The Corporation’s powers and duties later evolved to include marine surveying, naval stores inspections, pilot licensing, buoyage and beacon towers. ↩︎

- Chief Secretary’s Office Papers, National Archives of Ireland, CSO/RP/1819/57/A. ↩︎

- Chief Secretary’s Office Papers, National Archives of Ireland, CSO/RP/1819/57/B. ↩︎

- Chief Secretary’s Office Papers, National Archives of Ireland, CSO/RP/1819/57. ↩︎

- ‘Tramore Beacons, Tráigh Mhór’, December 1999, unpublished document based on the minutes of the Ballast Board, courtesy of The Commissioners of Irish Lights. ↩︎

- Specification and correspondence about Towers to be built on Brownstown Head, 1820, Devon Heritage Centre, 1262M/0/E/17/36, courtesy of Philly Dunphy. ↩︎

- Specification and correspondence about Towers to be built on Brownstown Head, 1820. ↩︎

- ‘Tramore Beacons, Tráigh Mhór’, December 1999. ↩︎

- Matthew Butler, ‘A Ramble in Gautier, Records of The Waterford Historical Society’, The Waterford News, 5 September 1947. ↩︎

- Specification and correspondence about Towers to be built on Brownstown Head, 1820. ↩︎

- Dublin Evening Post, 1 August 1820. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 30 May 1822. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 7 November 1822. ↩︎

- Commissioners for Auditing Public Accounts in Ireland, London 1821-25. ↩︎

- Freeman’s Journal, 13 January 1923. ↩︎

- R.H. Ryland, The History, Topography and Antiquities of the County and City of Waterford: With an Account of the Present State of the Peasantry of that Part of the South of Ireland, London 1824, page 246. ↩︎

- Irish Architectural Archive, Dictionary of Irish Architects 1720-1940, copy online at http://www.dia.ie/. ↩︎

- A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland, vol 1, London 2002, pages 293-94. ↩︎

- Walter G Strickland, A Dictionary of Irish Architects, vol 1, Dublin 1913, page 592; derived from Jack Tar, a common English term that was originally used to refer to seamen of the Merchant or Royal Navy, particularly during the 19th century. ↩︎

- Entract, J P, The Tramore and Kinsale Tragedies, 30th January 1816; His Majesty’s 59th, 62nd and 82nd regiments, London 1968. ↩︎

- ‘Tramore Beacons, Tráigh Mhór’. ↩︎

- William Gregory Wood Martin, History of Sligo, county and town, from the earliest ages to the present time, vol 3, Dublin 1892, page 224. ↩︎

- Waterford Mirror, 27 September 1823. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 4 September 1824. ↩︎

- Matthew Butler, ‘A Ramble in Gautier, Records of The Waterford Historical Society’, The Waterford News, 5 September 1947. ↩︎

- Waterford News, 4 August 1894. ↩︎

- Munster Express, 4 August 1894. ↩︎

- Waterford News, 1 June 1895. ↩︎

- Waterford Mirror, 3 September 1896. ↩︎

- Waterford Mirror, 25 June 1903 ↩︎

- Irish Emerald, 2 January 1904. ↩︎

- Kilkenny Moderator, 13 September 1905. ↩︎

- Kilkenny Moderator, 8 August 1908. ↩︎

- The Literary Lounger, 18 January 1911. ↩︎

- Cork Examiner, 24 July 1928. ↩︎

- Waterford Mirror, 25 June 1903. ↩︎

- The Dublin Leader, 21 July 1945. ↩︎

- Tramore Beacons, Tráigh Mhór’. ↩︎

- Munster Express, 19 April 1974. ↩︎

- Sunday Independent, 7 August 1977. ↩︎

- Kilkenny People, 12 August 1977. ↩︎

- Munster Express,23 January 1981. ↩︎

- Waterford News, 31 March 1989. ↩︎

- Waterford News, 2 June 1989. ↩︎

- Sunday Press, 10 September 1989. ↩︎

- Munster Express, 8 December 1989. ↩︎

- Munster Express, 21 August 1992. ↩︎

- Munster Express, 20 August 1993. ↩︎

- Waterford News, 12 September 2003. ↩︎

- The Mermaid Purse, Archive: The Battle for the Metal Man 2013, https://mermaidspurse.wordpress.com. ↩︎

- Tramore Beacons, Tráigh Mhór’, December 1999, unpublished document based on the minutes of the Ballast Board, courtesy of The Commissioners of Irish Lights. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Shipwrecks Tramore Bay Cancel reply