Ireland in the seventeenth century has been aptly described as ‘a land of blood and ashes.’[1] It was the time when the last bastions of the old Gaelic order were finally swept away by rebellion and conquest. At the beginning of the century all the townlands in the area around Tramore were owned by branches of the Anglo-Norman sept, the Powers, who although gaelicised and catholic, were still subservient to the English crown. The conflict between Anglo-Norman and Gaelic traditions and the widening influences of English governance created a fraught landscape, where loyalty and resistance coexisted.

Tramore itself was in the possession what appear to be two separate branches of the sept: The Powers of Guilcagh and the Powers of Adamstown. At the turn of the century, William Duff Poer or ‘Black William Power’ who was born circa 1540, held the lands at Guilcagh, Smoor, Knockaderry and thirty acres at Tramore which he had inherited from his brother Peter Power upon his death on 5 May 1563.[2] This William Duff has the distinction of being the first named resident of Tramore, as he was mentioned as being ‘of Tramore’ in a Tudor Fiant dated 11 May 1567.[3]

Maurice Power of Adamstown owned the remaining part of the townland. Maurice died on April Fool’s Day 1620, leaving his widow Elyna behind. An Inquisition Post-mortem into his death was taken at Tallow on 24 July 1620. This was a record of the death, estate, and heir of one of the king’s tenants-in-chief, in which it was stated that Maurice was seized of the lands of Adamstown, Tramore, and Ballingarrane: and they say that all and every one of the premises in Adamstown and Tramore is held by the decree of King James I by military service. Maurice’s first-born son Henry was confirmed as his heir. This Henry then married Margaret, the daughter of Henry Lee of Waterford in 1615 and had a son named Maurice.[4]

Accordingly, on the eve of the great Irish rebellion of 1641 we find that William Power, a Justice of the Peace, residing in Guilcagh and Maurice the son of Henry Power of Adamstown were the proprietors of Tramore. While Great Newtown was part of the property of Walter Power of Castletown, where he lived in a ‘faire stone house’. The Powers of Garrancrobally had by marriage inherited Kilbolane Castle and lands in County Cork and so it was that Thomas Wadding, an alderman of Waterford became the new proprietor of that townland, who while residing in the city was also the owner of several townlands in the parish of Drumcannon including Ballynattin, Ballycarnane, Duagh and Monvoy. John Power of Dunhill owned Ballydrislane, Carrigavantry and Pickardstown. Coolnacoppogue was also owned by a John Power.[5]

The Great Rebellion

Following growing religious frictions in the late 1630’s the catholics of Ireland rose in rebellion on 23 October 1641. The rebellion began in Ulster with a series of attacks against the settler protestant population and then spread throughout the country involving an unlikely alliance of Gaelic and Anglo-Irish forces. The rebels formed a government named the Catholic Confederation to rule the area of the country under their control. At this time, Waterford City was under the control of its protestant mayor, Francis Briver, who opposed the rebellion. However, in March 1642, when a large rebel army appeared at the walls of the city, with much of the county out in rebellion, the catholic population within revolted and opened the gates. All the protestants living in or around the city were rounded up and expelled.

Naval activities around Tramore Bay were discussed on several occasions in parliamentary papers during the rebellion. The bay was subject to observation by parliamentary forces, as confirmed by Captain Thomas Plunket of the ship Crescent, on 13 December 1642, when he stated in a report to the House of Commons, that he positioned himself seven leagues off the coast, prepared to intercept any vessels coming from Wexford, Tramore Bay, or Dungarvan.[6] Moreover, on 31 December, Captain Francis Oliver, a native of Flanders, received a commission from the Supreme Council of the Confederate Catholics of Ireland to engage enemy shipping. His mission involved preparing his ship, the St Michael the Archangel, to conduct operations against the enemies of the crown, as well as adversaries of the catholic cause. Captain Oliver was directed to deliver any captured vessels to Wexford, Dungarvan, Tramore Bay, or any other harbour under the control of the Confederates.[7] However, a copy of the document was intercepted in March of the following year and later described in parliament as a ‘Commission of the Rebels in Ireland to one Francis Olivers, to commit piracy at sea’.

Following the execution of King Charles I in 1649, Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army landed at Dublin in August that year. The towns of Drogheda and Wexford were soon captured and thousands of the people sheltering there were slaughtered. In November 1649 Cromwell’s forces were outside the walls of Waterford City. However, they were unable to take the city, and instead laid rampage to the surrounding countryside, destroying the castles of Dunhill, Kilmeaden and Butlerstown. Soon afterwards, Cromwell left Ireland and returned to England, never to return. However, Waterford later fell to the Parliamentary forces of General Henry Ireton after an artillery bombardment of the city. Nearly all the catholic landowners in the area were dispossessed. John Power, the Baron of Dunhill and Kilmeaden and many others were transplanted to Connaught and their lands confiscated. The proprietors of Tramore, William and Maurice Power were both transplanted, as was James Power fitz William of Castletown. Thomas Wadding’s estates were also confiscated but rather than going to Connaught, he emigrated to France where he died in poverty. And so, the old order was swept away.

Following the restoration of the monarchy in the person of King Charles II, an inquisition was taken at Blackfriars in County Waterford on 9 February 1662 before Richard Power and others with ‘the oaths of good and lawful men’. Thomas Wadding, who was an alderman of the city was indicted for high treason. The jurors said that he, among diverse other persons, malefactors and traitors unknown did ‘imagine, contrive and compose rebellion, levy war and commit high treason’ against King Charles I on 23 October 1641. In 1641 and 1642 he acted very favourably in promoting the rebellion in Ireland. He attended several public meetings for electing the Supreme Council and County Council and was appointed to oversee a mint house in the city. It was further stated that he lived on his estates unobstructed in rebel held territory from 1641 to 1646 and in the first year of the rebellion, he ordered his brother Paul Wadding and two of his servants to ‘rob, take, drive and carry away the goods and chattel’ of Thomas Coote of Garrancrobally and Robert Pottle of Rosduff. At a meeting on 23 July 1646, he arranged for the reception of ‘Germanus, the Pope’s nuncio, with discharging artillery for him and providing him with ‘wine, saffron, bread and other necessaries for his accommodation.’[8]

Walter Power of Castletown was also indicted for treachery, rebellion, levying war, and high treason. He was also able to live comfortably on his estate which was within the rebels’ quarters from 1641 until 1647. He sent forth men and arms to assist the rebels and to contribute money to the carrying on of the rebellion in Ireland against the king. The jurors further said that on 23 October 1641 and until his death, he was the proprietor of the lands of Castletown, Newtown, Ballykinsella, Garrarus, Lisselan, and several other townlands in the baronies of Middlethird and Gaultier. The jurors then testified that William, his son and heir also acted in rebellion, levied war, and committed high treason. William Power lived in Great Newtown which was within the rebels’ quarters. He was one of the commissioners for raising and applotting money for the carrying on of the rebellion and acted amongst the rebels against the King, contributing men, arms, and money to the cause. It was testified that on 5 March 1641 together with other Irish rebels they stripped the wife of Edward Wade and about three hundred more English refugees at Passage.[9]

In their absence following the transplantations, the Powers of Tramore and Castletown faded from local memory. It was not until 1793 when Nicholas Power, who likely was a descendant of Black William Power, bought up Bartholomew Rivers property that the Powers would hold land in Tramore again. Writing on 5 June 1841, the historian J. O’Donovan stated that in the southeast part of the townland of Castletown there was a small fragment of the wall of a castle from which the townland took its name, but that no tradition existed as to who was its original founder or last occupier.[10] Canon Power noted that Cullen Castle was another of the Power castles and that according to popular account the nearby mansion house which was a residence of a branch of the Powers was in ruins since the transplantation period.[11]

Land Redistribution

Following the Cromwellian Conquest, it remained for the spoils of war to be distributed among the victors. To do this, a series of land surveys of the country were undertaken between 1654-56, reflecting the significant political and economic changes of the era. These surveys were not merely administrative tasks; they bore witness to the profound shifts in land ownership that would resonate through generations. In the survey of the Barony of Middlethird, dated 2 July 1654, the parish of Drumcannon was described as such: ‘the soil is generally arable and pasture and some bog… In Drumcannon and Quilly there is a stone house, thatched and the ruins of a church. In Garrancrobally, a mill and stone house both in repair, and in Great Newtown a thatch house with many cabins scattered up and down the parish’.[12]

The English economist William Petty conducted what has been referred to as a ‘census’ of Ireland between 1654 and 1659, commissioned by the Cromwellian government as part of the Down Survey. However, contemporary research suggests that this endeavour was more akin to a poll tax focused on heads of household rather than a comprehensive census of the population. The recorded figure for Tramore stands at ten.[13] Whether this number accurately reflects the entire population or merely the count of taxable heads of household in the townland, it undoubtedly appears to be considerably low, indicating a significant paucity of residents in the area. This circumstance likely denotes Tramore’s peripheral positioning, being isolated from more populous and economically thriving regions; moreover, it may partially stem from the conquest, which disrupted established ways of life and resulted in the displacement of numerous families.

In the survey conducted in 1654, Tramore was documented to encompass an area of 222 acres, of which 204 acres were designated as arable or utilized for pasture, while eighteen acres were categorized as bog. The Rabbit Burrows, known as Duaghmore, accounted for an additional 142 acres, one hundred acres of which were identified as sandbank. Consequently, the cumulative acreage for Tramore reached a significant total of 364 acres. These lands were allocated under the Acts of Settlement and Explanation to Henry Nicoll, a captain in the parliamentary army, in acknowledgment of his contributions during the conflict, as well as to Lord Power of Curraghmore. Nicoll was awarded 176 acres of productive land, whereas Lord Power received the remaining twenty-eight acres.[14]

Moreover, the forty-two acres of arable land situated in Duaghmore were evenly apportioned between Nicoll and Lord Power. However, Nicoll entered into an agreement with Arthur, Earl of Anglesey, who acted as guardian for the heir apparent to Lord Power, who was described as a lunatic. This agreement, finalized on 14 July 1663, enabled Nicoll to attain sole ownership of a considerable tract of land within the Barony of Middlethird. This extensive landholding included not only Tramore but also Newtown, Coolegoppoge, and Kilmeaden, aggregating an impressive total of 5610 acres by plantation measure in County Waterford alone. As a result of this consolidation, a patent dated 11 June 1667 was duly issued, stating that ‘in pursuance of a certificate and decree of the Court of Claims’, all 204 productive acres of Tramore were granted to ‘Henry Nicoll, his heirs and assigns forever’[15] This underscored the significance of legal documentation and patents in establishing land ownership in the aftermath of the conflict. Additionally, Nicoll was granted huge tracts of land in other counties including hundreds of acres in the parish of Kilbolane, County Cork, which had been confiscated from the Powers, the previous owners of Garrancrobally.

Henry Nicoll

Who exactly was this Nicoll, to be granted such vast amounts of property? Nicoll hailed from Cornwall and was the son of Humphrey Nicoll of Penvose and Phillipa, the daughter of Sir Anthony Rowse of Halton. His prominence in Irish land ownership was largely due to his notable role in the restoration of the monarchy following the death of Oliver Cromwell. It was noted in parliamentary records that he was extremely active in efforts aimed at reinstating the monarchy, and his commitment was reflected in the large sums of money he personally expended for this cause.

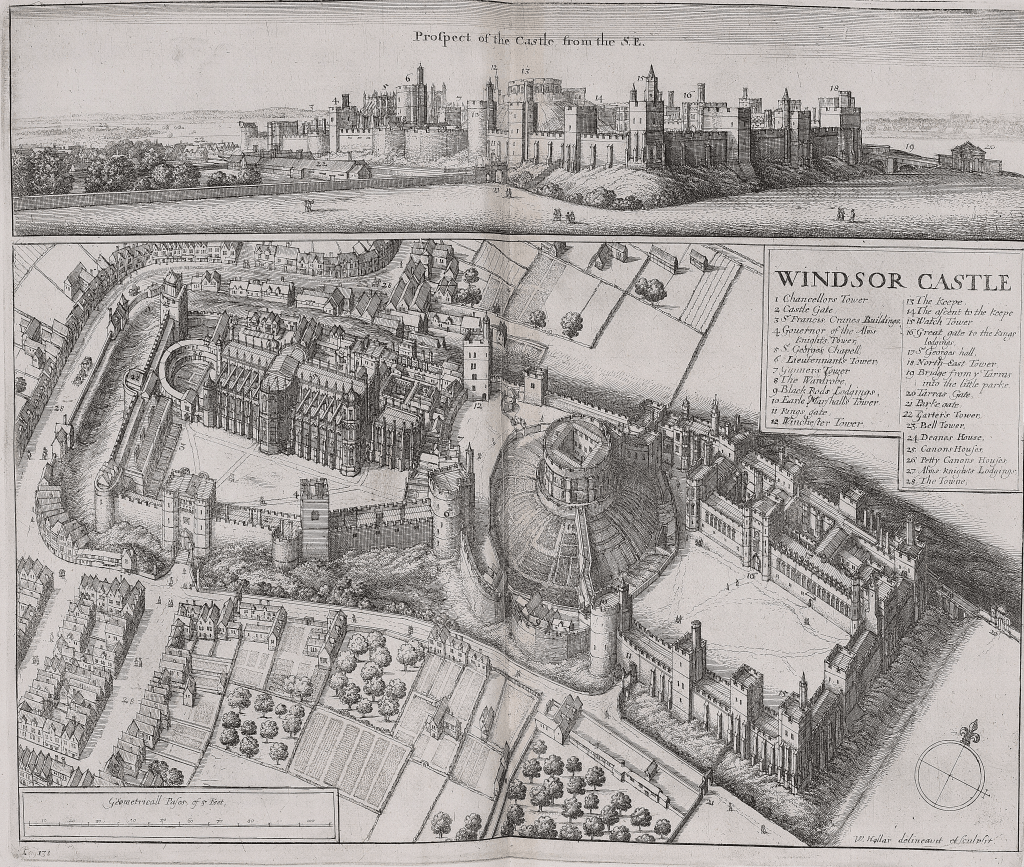

A pivotal moment in English history arose in January 1660, when General Monck, the commander of the parliamentary army of occupation in Scotland, marched on London to counter a military coup against the Rump Parliament. In a show of loyalty and support, Nicoll met General Monck at Nottingham, armed with petitions from gentlemen in Devonshire and the western counties advocating for a restoration of parliamentary governance. Recognizing his loyalty and aware that Nicoll was acquainted with the garrison of Windsor Castle, Monck entrusted him with the critical task of its capture. A task which he accomplished with great skill and stealth, catching the garrison by surprise, and securing valuable military stock, including arms and ammunition.[16] Following the strategic capture of London, Monck supported free elections to parliament. These elections led to the formation of a moderate parliament that proclaimed Charles II king on 8 May 1660.

After the restoration of the monarchy, Nicoll established his residence in Kilmeaden, yet he found himself confronted with significant financial burdens. Although ambitious plans for his Irish estates had been conceived, a third of his lands faced expropriation, leading to substantial expenses associated with maintaining the remaining holdings, thereby encumbering his estate. Hoping to alleviate this financial strain, Nicoll resorted to cutting down a large quantity of timber from his estates in Waterford. This timber was intended for the reconstruction of London following the catastrophic Great Fire of September 1666, an event that devastated a sizeable portion of the city. However, when Nicoll sought to hire shipping for transporting this timber, he found the costs prohibitive and ultimately unprofitable. To further his objectives, he made the decision to purchase two prize ships, namely the Sea Fortune of Amsterdam and the Wild Boar, investing £1000 in this venture to ensure the timely delivery of the timber.[17]

On 17 October 1667 Nicoll petitioned the king for an abatement in the price of the two prize ships. He claimed that he ‘deserved to be very well rewarded because of his early activeness for the restoration, where he ‘expended considerably therein and received no recompense’. Consequently, he was granted the Wild Boar at £276 9s, with a year allotted for payment. However, after incurring substantial expenses related to rigging and preparing the vessel for sea, the Wild Boar foundered during its voyage, resulting in the loss of fifteen men and depriving Nicoll of the means to transport the timber or settle his debts. Nicoll subsequently petitioned the king for a grant of the ‘Golden Hand fly boat with all her furniture and apparel’ at the same price and terms as he paid for the Wild Boar, while also seeking orders to be issued to the Duke of York and the navy Commissioners to give him immediate possession of the ship. The king consented to grant Nicoll the ship at a reasonable price, acknowledging his ‘early activeness and great expense’ in contributing to the restoration.[18]

In May 1668, identified as Major Henry Nicoll of Kilmeaden, he was contracted by the Admiralty to clear the River Medway of the wrecks sunk there as part of the river’s defences. He was given six months to complete the contract and was given several fly boats and other equipment necessary for the task. However, Nicoll alleged that because the boats and equipment were defective and that those appointed to repair them were negligent in their work, he incurred losses amounting to £1,000 and upwards. Despite seeking restitution, he was subsequently pursued in a legal action for £2,000 for non-fulfilment of his contractual obligations. Fortunately, on 1 July 1669, a Treasury warrant was issued to stay proceedings against him, indicating that he still maintained some favour with the crown.[19]

Unfortunately for Nicoll, he remained heavily indebted and resorted to mortgaging his property multiple times. On 26 April 1669 he mortgaged his lands to three English gentlemen, namely Edmund Fortescue, William Barrett, and Anthony Trathewey for £2,000.[20] The following year he also mortgaged part of the townlands of Tramore and Knockaderry to Thomas Wyse of London. Wyse was to retain a significant interest in the properties for over twenty years.[21] Some of Nicoll’s subsequent legal wrangles arose from tenants that were paying rent to him that was rightly due to other leaseholders.

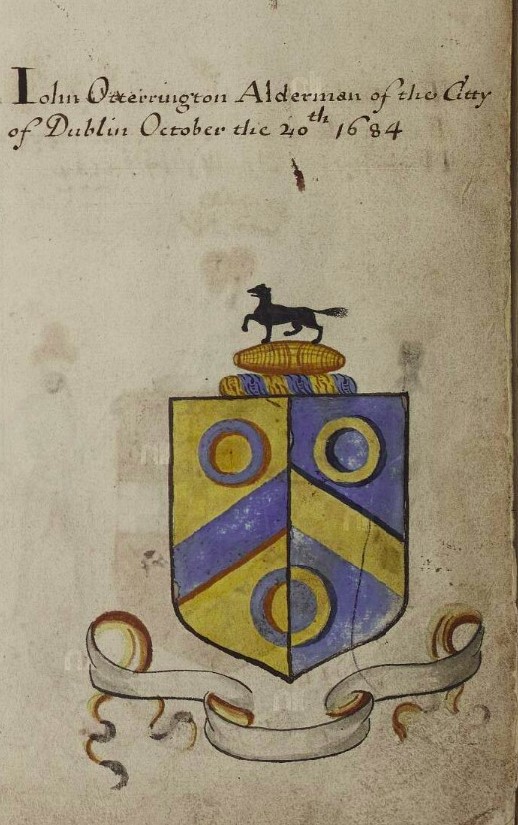

On 23 January 1671, Nicoll mortgaged 10,200 acres to Sir Andrew Owen for £2,100.[22] Sir Andrew later passed away, after which his widow, Lady Anne Owen, née Hawkins, married Sir Arthur Loftus in December 1676. By this juncture, Nicoll also had assigned his property in a deed dated 24 December 1675 to John Otterington, a merchant from Dublin, who subsequently acquired Loftus’s interest in the properties for the sum of £2,961 on 24 October 1677.[23] Nonetheless, Nicoll’s financial difficulties persisted. He accrued a debt of £800 to James Mell, another Dublin merchant. However, on 10 March 1676, John Otterington’s son in law, John Hayes of Dublin, purchased this debt with Otterington’s acquiesce. According to Otterington, his motives for buying up Nicoll’s debts were due to him ‘having a great kindness for Henry Nicoll and being concerned in his estate.’[24] In November of the same year Sir Miles Cooke, of London gained a judgement against Nicoll for £980. Nicolls relatives in Cornwall similarly faced financial adversity during this period. His brother Anthony, who died in 1678, had sold the manor of St. Tudy, together with Penvose, the seat of his ancestors, to alleviate his debts.

A Chancery decree dated 15 May 1682 determined that Nicoll was to be granted two years from 24 June to redeem the lands mortgaged to Otterington, encompassing thirty-one townlands in Middlethird, including Tramore and Knockaderry. It was stipulated that Otterington would be paid ‘£8 per cent per annum for his debt of £8000’ and be paid ‘£400 per annum clear’. Furthermore, Otterington was permitted to lease Kilmeaden, except for the manor house and adjoining lands reserved for Nicoll, to Stephen Worthevale at an annual rent of £240 for two years. Should Nicoll procure a buyer for the lands who would pay 14 years purchase, he could redeem the lands by paying Otterington the sum of £6000 along with accrued interest; failure to do so would result in Nicoll being forever barred and Otterington retaining ownership.[25] On 6 July 1683, Otterington, leased some of Nicoll’s lands back to him for 7 years at £320 per Annum.[26]

The dispute between Nicoll and Cooke over the £980 debt lay unresolved for many years, despite various subsequent agreements. Nicoll believed that he would find comfort in his later years if the matter could be settled amicably. In October 1683, Nicoll offered his stock of 4,000 sheep and five hundred young oxen as security to Otterington for the £980. However, on 5 July 1684 Cooke wrote to Otterington, ‘that the captain every year had the murrain amongst his black or white cattle or in his own brains’. Otterington subpoenaed Cooke in 1694 in an attempt to finally bring the matter to an end. On 8 February 1694 Nicoll wrote to Otterington, ‘When we have done our utmost, we must leave it to God. I believe it is not the first time you nor I have been frustrated in our expectations of the judgments of court but yet I cannot believe the matter will go as they think.’[27] Nevertheless, it appears that they lost the case.

On 10 December 1691 Otterington leased several townlands including Tramore to Nicoll in consideration of his willingness to give up, when demanded, his flock of 3,300 sheep in Co. Waterford. Nicoll was to have the benefit of the wheat already sown on the lands and allowed have free grazing for horses and black cattle until the following May providing that he gave Otterington the first refusal of the cattle when put up for sale. Despite his financial woes Nicoll represented Waterford city as an MP in the parliament of 1692. Nicoll died at Waterford in April 1705 at the age of eighty-one and was buried in Saint Mary’s churchyard, Kilmeaden, By which time all of his Waterford property had been transferred to Otterington. His memorial reads: ‘Here lies the body of Captain H Nicoll son of Humprey Nicoll of Penvose in the county of Cornwall and of Philippa his wife the daughter of Sir Anthony Rowse of Halton in the county of Cornwall. He died at Waterford the 31st of April 1705’.

John Otterington

The part of the isthmus on which the Rabbit Burrows stand was marked as Cape Otterington on all the nautical charts of Waterford Harbour from 1738 until 1835. John Otterington was an alderman of the city of Dublin in the late 17th century. However, he sometimes found need to avoid his civic duties, perhaps due to the demands of his business interests or personal affairs. On Monday 24 September 1677, he was excused from serving the office of sheriff upon paying the sum of £60, a substantial amount that reflected the value placed on civic roles in the community.[28] Furthermore, in a letter dated 31 January 1686, he asked to be excused from the table of alderman ‘since it had pleased his Majesty to demand his constant attendance at the affairs of his Majesty’s Revenue’, which highlights the often-conflicting obligations faced by public officials in balancing their duties to both the city and the Crown.[29] Nevertheless, despite his absences, he was elected Lord Mayor of Dublin on Monday 18 August 1690, a testament to his influence and reputation in the city. Following his time as mayor, on April 4, 1692, he was elected Justice of the Peace for the county and city, further solidifying his standing as a key figure in the local government and legal system. However, shortly afterwards he moved into Henry Nicoll’s former house in Kilmeaden while still serving as a JP for Dublin.

In 1696 there was a growing concern and subsequent complaint that Otterington had increasingly absented himself from Dublin and did not attend the quarter sessions, a critical aspect of maintaining law and order. It was reported that ‘he lived remote in the country for above three years past, where he still inhabits and resolves to continue,’ indicating a significant detachment from his duties, which many felt undermined the effectiveness of the local justice system. This absence was perceived not only as a personal choice but as a serious dereliction of responsibility, especially given the increasing demands on justices to oversee the burgeoning number of cases that required their attention and adjudication. He was accused of neglecting public affairs and failing to attend the court sessions, which were likely to suffer the consequences of having too few justices present, a situation that would prove ‘of very ill consequence and prejudice to the city’ as it could lead to a breakdown in the administration of justice and an increase in lawlessness. Consequently, it was ordered that he be displaced from his office of Justice of the Peace, and that some other fit person residing in the city be chosen in his stead.[30]

It is noteworthy that by this time Otterington was serving as high sheriff of Waterford. He was reputed to have developed the estate of Kilmeaden and brought families from Ulster to settle there. However, his foremost tenant in Waterford was Stephen Worthvale, another Cornishman. When Sir Richard Cox visited Waterford in the 1680s, he described Tramore Bay as ‘of no great note,’[31] highlighting the relatively unnoticed nature of the area, and suggesting that despite its natural beauty, it had yet to gain prominence as a location of significance in the landscape. Nonetheless, on 24 December 1698, Robert Cragg wrote to Otterington concerning a business opportunity in Tramore:

For the worthy Alderman Otterington

Waterford 24 December 1698

Worthy Sir,

I thank you for the advice; that you did concern the thoughts about the landing of salt and other stores at Tramore Bay and likewise of shipping of herring from there; which hath been duly considered and find it practicable to either load or unload there and with as little charge as if at Waterford Quay and with a small charge a vessel of 30 or 40 tons may sail up in to the storehouse door safely to load or unload, there being a freshwater stream that comes out of the land and empties itself into this bay. There is no difficulty in this matter and it all can be got at no charge; of bringing stores to and from the place; the extraordinary charge will not amount to a half penny per barrel.

I have agreed in the whole for the premises and on Thursday I am to settle the whole covenants: at a rent not exceeding 10L per acre: with other good articles as that he shall not let or suffer any other person to build or fish in the bay, but our company. And all the tenants that now are or shall be there after shall be obliged to keep such adequately of nets as we agree of and to let us have all the fish at 6d per meas cheaper than they are at other markets: if I accept of them, if not I have power to refuse them, but they cannot dispose of them without my license: and many other good exchanges too long to repeat. I am your obliged servant.

Robert Cragg

Pray Col Nicholls silent for a week or 10 days until we have sealed.[32]

Unfortunately, no further correspondence between the two men appears to have survived that could inform us as to how the venture fared. Nevertheless, this correspondence reveals a glimpse into the economic undertakings and ambitions of the time, where figures like Otterington were essential in fostering trade and enterprise within their locality. The strategic consideration of the bay for both the landing of goods and the shipment of local resources like herring illustrates an evolving market, while the existence of a storehouse in Tramore suitable for commercial activities of the scale suggested in the letter is intriguing and points to the place being connected to the hinterland by a rudimentary road network. The meticulous arrangement that Cragg details suggests a thought-out plan aimed at minimizing costs while maximizing returns for their venture. The clause regarding the exclusivity of their fishing rights implies a competitive edge they sought to maintain, ensuring that their business was not only sustainable but also flourishing. The location of the stream and storehouse is another question, Lady’s Cove being the most likely location. However, Otterington’s coastal properties included the entire townlands of Newtown and Tramore and the reference could refer to Newtown Cove.

Otterington was married to a Scottish woman named Mary Maitland, and together they had a daughter called Mehetabela, a name steeped in biblical significance, meaning ‘God rejoices’. On 24 February 1674 Mehetabela married John Hayes of Winchelsea, Sussex, England, and the couple later had a daughter named Elizabeth. Tragically, Mehetabela passed away in 1681, leaving behind her young daughter. In response to this loss, Otterington took it upon himself to provide for and educate his granddaughter. He then arranged for her to be married to Arthur St. Ledger and provided £3000 to her on the event of her marriage. The ceremony took place on 24 June 1690, when Elizabeth could have been no more than sixteen years old. However, this union was not without controversy, as her father vehemently opposed the marriage, claiming it had been orchestrated ‘in a clandestine way’.[33]

Adding complexity to the family saga, Otterington found himself embroiled in a protracted legal battle with his son-in-law, John Hayes. This dispute revolved around the non-payment of Mehetabela’s jointure, leading to Hayes successfully suing Otterington for the significant sum of £2,000 in June 1684. Following the ruling, Otterington was granted a two-year abatement on the interest owed, deemed a reasonable allowance for the maintenance of Hayes’s child.[34] Seeking to rectify what he believed was an unjust ruling, Otterington appealed the verdict in December 1692 before the House of Lords, with Arthur St. Ledger stepping in to support him. Nevertheless, the original ruling was upheld on 19 January 1693, leaving Otterington in a precarious position. Despite the initial hostilities, evidence suggests that by August 1693, the situation between the two men had improved; Hayes was able to inform Lord Tweeddale that ‘all differences are composed’, indicating a compromise had been reached.[35]

As the life of John Otterington drew towards a close, he wrote his last will, dated 23 April 1701.[36] It is believed he passed away shortly before 18 July 1701, the date marking his replacement on the Board of Aldermen of the city of Dublin. His will was subsequently proven on 2 June 1702 in the Canterbury Prerogative Court, revealing that he owned property beyond the shores of Ireland. It appears that he left all his property to his granddaughter, Elizabeth. In return, she honoured her grandfather with a tomb erected in Saint Mary’s churchyard, Kilmeaden. Her legacy continued as she became Viscountess Doneraile, and Lady Elizabeth’s Cove in Tramore bears her name, symbolizing her lasting impact on the region. The Donerailes would go on to hold title to the lands of Tramore for the next two centuries.

[1] Aodh de Blácam, Gaelic literature surveyed: from earliest times to the present, Dublin 1973, pages 133-34.

[2] Livery of William Duff Poer, Extract from patent roll, NAI Lodge/18/798, virtualtreasury.ie.

[3] ‘Fiants of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth’, The Eleventh Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records in Ireland, Dublin 1887, page 158, no. 1046, page 157.

[4] Inquisition Post Mortem, Maurice Power, RIA OS EI/75/30, virtualtreasury.ie.

[5] The Down Survey of Ireland, downsurvey.tchpc.tcd.ie.

[6] Historical Manuscripts Commission, The Manuscripts of His Grace the Duke of Portland, preserved at Welbeck Abbey, London 1891, page 78.

[7] Calendar of State Papers Ireland Charles I, London 1900, page 376.

[8] Inquisition Post Mortem, Thomas Wadding, Royal Irish Academy, RIA OS EI/77/71, virtualtreasury.ie.

[9] Same.

[10] John O’Donovan, Ordnance Survey Letters: Waterford, 14/G/7/5(6), Royal Irish Academy, askaboutireland.ie.

[11]Rev Patrick Power, The Placenames of Decies, London 1907, page 384.

[12] ‘The Down Survey Maps of County Waterford, Part Two’, Decies Journal of the Old Waterford Society, Spring 1992, pages 13-16.

[13] Seamus Pender, A Census of Ireland, Circa 1659, Dublin 1949, page 344, irishmanuscripts.ie.

[14] ‘The Down Survey Maps of County Waterford, Part Two’, Decies Journal of the Old Waterford Society, Spring 1992, pages 13-16.

[15] Document respecting Grants made by the Crown to different persons of the sands of Tramore, CSO/RP/1820/1227/18.

[16] Calendar of State Papers, Domestic, Charles II, London 1866, Pages 531-32.

[17] Calendar of State Papers, Domestic, Charles II, London 1866, Pages 531-32.

[18] Henry B Wheatley, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, vol VII, London 1896, page 154.

[19] Calendar of Treasury Books, Volume 3, 1669-1672, Warrants Early XXXIII. p. 111.

[20] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 48326/6.

[21] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 48326/7.

[22] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 32,916/9.

[23] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 48326/15.

[24] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 48326/18-19.

[25] Chancery Decrees, NAI RC 6/2, virtualtreasury.ie.

[26] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 48326/17.

[27] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 48326.

[28] Monday Books of The City of Dublin A.D. 1658 – 1712, Page 69.

[29] Monday Books of The City of Dublin A.D. 1658 – 1712, Page 84.

[30] Monday Books of The City of Dublin A.D. 1658 – 1712, Page 84.

[31] Julian C Walton, ‘Two Accounts of Waterford in the 1680’s’, Decies Journal of the Old Waterford Society, Autumn 1987, page 30.

[32] The Doneraile Papers, c. 1607-1950, National Library of Ireland, MS 48327/10

[33] Julian C Walton, Unpublished notes and transcripts on the subject of John Otterington.

[34] John Hayes Biography, https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/.

[35] Same.

[36] John Otterington Will, National Archives Kew.

Leave a comment