Growing up in Tramore I was always intrigued by stories of the otherworldly spectre haunting the Rabbit Burrows known locally as the Guramooghagh or some such variation of the name. In his book, Placenames of the Decies, the Canon Power referred to a place called the Gormog’s Garden on Tramore Burrow, explaining that Gormog or Gormogach was ‘a spirit who haunts the desolate sand wastes’.

The Guramooghagh hit the headlines under a different name in the Autumn of 1929, when strange lights were reported to be emanating from the Rabbit Burrows and it was suggested locally that the source was none other than the ‘Goolamooluck Man’s lantern’. On 29 November 1929, the Waterford News ran two articles about the spectre. In the first an old Gaelic speaker was quoted as saying that the word ‘Goolamooluck’ meant ‘the back of the mud’. The article continued that the spectre was alleged to have appeared on Tramore Strand in the 1820’s. Some of the stories told recalled the fairy tales of Hans Christian Anderson, but with a dollop of realism introduced by the assertion that his name was Power and that he kept a public house in the burrows where old Tramore men would gather, particularly on Sundays. Another informant stated that a portion of the Rabbit Burrows was called the Goolamooluck’s Garden. This ‘enchanted garden’ was like nothing seen elsewhere and was described as quite large, standing high above the strand, containing growths of Pegwood or Witch Hazel Privet, which showed a delightful pink blossom. The place had all the appearance of being cultivated at one time. Grandparents related to their grandchildren in Tramore that it was next to impossible to find the garden but once in it, one could not get out and that it could not be found a second time. The speaker speculated that it was quite possible that smugglers or land pirates would have such a habitation and that the tradition about the light to lure vessels to the Burrow was quite likely too. The idea of anyone getting into it and not being able to get out again may be explained simply by the probability that smugglers or robbers did not want their hiding place known. He added that it might be worthwhile to excavate the garden for evidence of ancient activity. There was a tradition among the people of Garrarus that the Goolamooluck’s light glides in by Brownstown Head to the Burrows for several nights before a storm.

The second article stated that the tradition survived among Tramore folk that many years ago a quaint old man kept a stall in the vicinity of the Rabbit Burrows where he supplied visitors with refreshments. When a storm was approaching, he moved along the lonely strand swinging a light by night in the hope of luring dubious sailors to catastrophe and with the intention of looting. He was a weather prophet of no mean order and when the Goolamooluck’s light was seen moving along the strand Tramore folk prepared for a storm. A resident of Tramore believed that he recently saw the light along the strand moving over Brownstown and entering the cave at the Rabbit Burrow where the subject of the traditional story is said to have resided. Then there is the folktale of a white horseman who used to ride furiously along the sea front. A slaughter diviner, a psychic personage akin to a water diviner claimed to have traced in the Burrows, the keening of the souls of warriors in some prehistoric battles slaughtered there.

In a letter published on 6 December, Joseph Power from Garrarus stated that he had made inquiries amongst the old native Irish speakers in the district, and it seemed that the original word was mispronounced or misspelled. It was a mixture of Irish and English, the word ‘goola’ being a distorted way of pronouncing ghoul which signified a wicked evil spirit and the last part of the word ‘mooluck’ which meant a quagmire akin to the sucking quicksand and slob around the Burrows. As far as he knew the explanation of the word Goolamooluck was ‘the evil spirit of the quagmires.’

On 31 March 1930, Bertram Poole, the well-known Waterford City photographer, wrote a piece on the Goolamooluck in the Cork Examiner. According to local tradition it was the ghost of a man who one time lived in a house in the sandhills and on stormy nights used to wave a lantern to entice ships to destruction. He would then take possession of anything of value that was swept ashore and as punishment was forced to wander around the sand hills on stormy nights, lantern in hand. People sometimes reported seeing the ghoul’s lantern moving across the Sand hills on stormy nights. Poole agreed that the name was Irish, and that the most convincing explanation of the name was the same as that of Canon Power’s Gormog, a ghoul or evil spirit of the waste place. He further noted that Professor Power had obviously never heard of the term Goolamooluck and that it was probably a newly invented name for Gormog. Poole himself recalled that the old people used to tell the story of the spirit called Gormog who haunted the sandhills and sometimes assumed the form of a black pig. It was clear to him that the story was a blend of ancient legends and more recent ones. Commenting on Poole’s piece in a later edition of the same newspaper, Edmund Keoghan, the Dungarvan photographer and local historian, stated that as a little boy growing up in Tramore in the 1860’s, he could not recollect having heard the name Goolamooluck, which struck him as a recent invention.

Nicholas Whittle wrote a fictional story called ‘The Wreck Light’ which was published in the Waterford News & Star in December 1930. In it he described the mysterious light that was always seen before a wreck in the bay. It was said that it was caused by the spirit of a wicked sea-captain who met a watery grave there, while others said that it was ‘the devil himself that could attract in ships to wreck them’. In a later article called ‘Legend and Beauty’ he talked of the ‘Golamoogie’, the phantom man who resided down in the sandhills and who moved about invisibly on his quests. His daughter, Breda Ryan was convinced that the Guramooghagh and the owner of the wreck light were different entities, stating that: Jack O’Lantern was a man who had a long pole with a lantern on top, he tied it on his leg, on bad dark nights he walked the beach, to ships it looked like a harbour with the light going up and down, it caused many a wreck, he was found out and dealt with, that was the story we knew as children, true or not ? Nonetheless, in Tramore, the widespread story of Jack O’Lantern seems to have become attached to the story of the Guramooghagh.

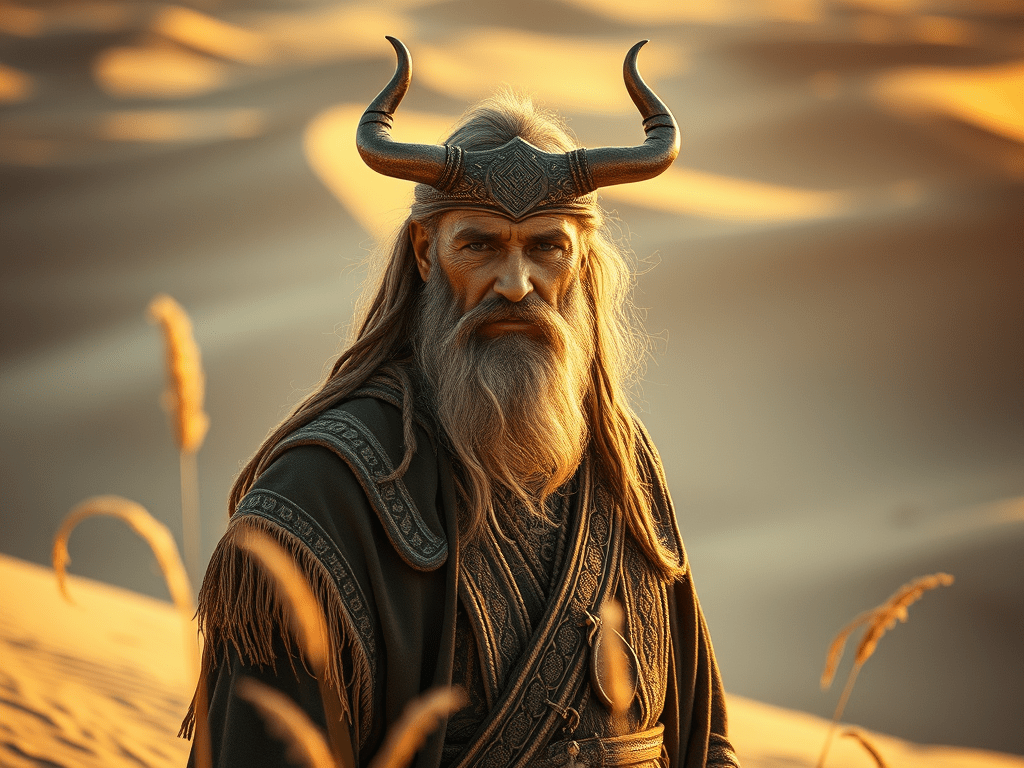

The Guramooghagh was mentioned several times in the Schools Folklore Project of the 1930’s in which school children collected folk tales, often from their older relatives. Ursula O’Sullivan of Tramore recited a story told to her by her grandmother Mrs C Power about the phantom of the Burrows who was seen one night every year. The ‘Gullamugee’ was a man dressed in armour on horseback who appeared in a garden. If anyone saw him, it was said that they would die within the year. There were also stories of him hiding treasure in Ballynattin, prior to having built a palace in the Rabbit Burrows and of riding out across the strand on his white horse before a storm. However, it was also believed that the Guramooghagh lived under the sea, and that apart from his visits by night to the Burrow, he never came nearer than the third wave to the shore.

Margaret Gear of Ballymacaw told a story about her great-grandfather who had a grey mare that used to graze on the small island in Rineshark where the coastguard station used to be. ‘One evening he went to fetch home the mare. He did not bring a bridle or anything as he knew she was old and quiet. He got on her back and away she went as fast as the wind, across the strand and around the burrow and brought him back to the same spot again and then disappeared. He thought at first that it was his son’s mare but then he concluded that it was the Garanoogah’s white horse.’

In yet another story the Guramooghagh had a small black cow which grazed among the sand hills of the Burrow. Sometimes the cow would come across the back strand to graze with the cows of the farmers there. There was a purse in her left ear which held an unspendable shilling. No matter how often the shilling was taken out, a shilling always remained. Often men tried to catch her, but she raced away from them, straight to the Burrow and under the sand. It was said to be lucky to have her amongst the cows. ‘When they give extra milk on a summer’s morning people say that the Guramoogach’s cow was in amongst them during the night.’ Cows did actually graze on the Burrows in times gone by. An advertisement in the Waterford Mirror for the sale of the Rabbit Burrows in 1802 stated that there were upwards of 100 acres of excellent grazing ground fit for young cattle.

The historian Ged Martin was under the impression that the Guramooghagh was forgotten in modern-day Tramore. However, the stories were still told when I was a boy in the 1970’s. Furthermore, R. Byrne recorded three variations of the name of the spectre in his article ‘Irish words still in use in the Fenor area’ Decies, 26, 1984, Gurramú, Gurrucha and Gurramuchal. Ged Martin also came to the conclusion that the legend originated from some ancient source that later merged with the story of a corrupt coastguard, who was caught assisting smugglers, and rode off into the sea. He recounted a story of when the poet Wilfred Owen visited Tramore as a child in 1902 and the family encountered a ghostly apparition who appeared before them in the mist, gesticulating in a threatening manner, before disappearing. ‘Back at their lodgings, the Owens recounted their adventure, but their hosts, the Fleurys did not wish to know. Indeed, the visitors were urged not to mention the episode to anybody.’ Martin thought that it was likely that the Fleurys believed their visitors had encountered some manifestation of the Guramooghagh and that, at the very least, it would be bad for business if the story got around. Martin was at pains to note that the family were Church of Ireland, and that Protestants may have believed in the Guramooghagh just as fearfully as their Catholic neighbours.

In Canon Power’s book of placenames, the name ‘Uaim na Maolac’ the meaning of which was unknown, is given to a cave at Brownstown Head. Uaim na Maolac, can be interpreted as the cave of the Maolac. Possibly the ghoul’s name was derived from ‘Ghoul of the Moloch’, one of the devils mentioned in the Bible. Of course, it was a widely spread early Christian practice to take the gods of the old religions and turn them into the devils of the new.

In the journal At the Edge published in March 1998 Greg Fewer wrote of ‘The Guramooguck’. He noted that the tradition warning that anyone seeing the Guramooghagh was set to die within the year, hinted that he was a form of Donn, the otherworld God of Irish mythology. In Irish folklore Donn was the god of the dead who lived beneath hills and was often seen riding his white horse on the strand before a storm. Donn was also widely associated with shipwrecks and sea storms, cattle, and crops. Fewer expressed amazement that any tradition relating to an ancient deity had survived in an area where the earliest figures in folklore tended to be those of the local patron saint.

One localized variant of the deity of particular interest to us is ‘Donn Dumach’, or Donn of the Sandhills who was believed to reside in the burrows of Doughmore in County Clare, an area very similar to Tramore Burrows. In fact, the old name for the Rabbit Burrows of Tramore was Duaghmore as recorded in the Down Survey 1656-58. The name comes from Dumain Mór which means ‘great sandy warren’. Both places are peripheral locations and as such were sometimes regarded as distinct from the human realm, places imbued with legend, myth, and beauty. There is a poem entitled ‘Donn of the Sandhills’ written in the mid-1730s, by Aindrias MacCruitín who was a seanchaidhe and poet of considerable repute. With the destruction of the Gaelic order in the late 17th century, Gaelic scholars and poets lost much of their patronage and suffered a reduction in income and status. In his poem, MacCruitín calls on Donn to grant him shelter in his enchanted palace in the sandhills. From the poem it is evident that MacCruitín saw Donn as a son of the Dagda, a deity of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

Leave a reply to chieftotallye61dd76255 Cancel reply