There are several ghost stories associated with Tramore, the most famous of which is the spectre known as ‘The Guramooghagh,’ a mysterious figure who is believed to haunt the Rabbit Burrows. Other captivating stories include the Ghost Band of the Sea Horse, a spectral ensemble said to play a haunting melody on stormy nights, and the Phantom Ship, which locals from bygone days insisted could be spotted on the horizon during misty evenings. Additionally, legends speak of a mysterious White Horse that roams the strand under the moonlight, and even a headless horseman has been sighted galloping through the fog. Then there is the chilling story of the Haunted Well on the Cove Road, rumoured to be a source of strange phenomena, that in simpler times drew in curious visitors eager to experience its supernatural reputation.

The Haunted Well

For many years, the freshwater spring at the base of the steps leading from the Doneraile Walk to the Cove Road was appreciated for its cool waters by thirsty cliff walkers during the warm summer months. The inscription on the keystone of the archway constructed over the well dates its establishment to 25 August 1859, marking it as a minor historical point of interest. Over time, a legend emerged that spirits could be observed here at midnight, an eerie phenomenon that became embedded in the town’s folklore. Notably, the story of the Haunted Well does not appear in written form until the early 20th century and although the story may have been transmitted orally prior to that time, its origins are challenging to discern.

Nonetheless, the source of the tale in its modern form can be traced to an accident that occurred on Saturday, 6 July 1901 when a laundress named Mary Holohan, who lived on the Cove Road, was tragically drowned at the well under rather peculiar circumstances. It appears that she left her house at about ten to midnight going by the Doneraile Walk to get a can of spring water from the well. Mrs. Browne, with whom she stayed, became anxious when she had not returned after twenty-five minutes and went down to the well to see what delayed her. There, she was horrified to find her dead body slumped over the well. she cried out in terrible fright, and two young men came to her assistance. They lifted the body away for a short distance and the priest and doctor were sent for. Father Walsh and Doctor Stevenson arrived quickly, but the woman was beyond all spiritual or medical aid.

An inquest was held into the circumstances of the death on 8 July when the well was described as no more than four or five feet in circumference and the water within was only seven or eight inches deep. However, to obtain a supply of water it was necessary to stoop over and it was evident that the woman while bending over to fill the pale took a weakness and fell headfirst into the well and suffocated. Edmund Power, the coroner returned a verdict of accidental death by drowning.1 However, the mysterious circumstances of her demise horrified the community and led locals to suspect that the unfortunate lady died from fright, having seen a ghost, and her story quickly became part of local folklore.

Similarly to the tale of the hopping maidens associated with the Metal Man, the story of the Haunted Well appears to have gained traction through the postcards of the Poole and Lawrence photographic companies. Arthur Henri Poole certainly had a penchant for featuring ancient legends; his advertisements in the 1919 edition of A Guide to Tramore invited people to visit the wishing well at Reginald’s Tower, accessible through his business premises!2 Two of the Lawrence postcards showcase photographs attributed to Robert French, depicting the same elegantly attired women captured at two different wells in Tramore. One photograph was taken at ‘The Wishing Well’ located on the steps leading from the Doneraile Walk to Foyle, accompanied by the caption: ‘It is said the water from this well is a good cure for rheumatics.’ The second photograph portrays ‘The Haunted Well’, bearing the caption: ‘It is said spirits are often seen here at midnight.’ Both postcards are believed to have originated around 1908. The earliest reference to the well being haunted in a newspaper comes from an edition of The Irish Independent published in June 1911, which included a full-page article on Tramore entitled ‘The Gem of the Southern Shore’ that featured a picture postcard of it.3

On the 1901 Census, both Mary Holohan and her 26-year-old son, Michael, were described as illiterate, which adds another layer to their story. Michael doesn’t appear in Tramore on the 1911 Census. What happened to him remains a source of curiosity and speculation, leaving one to wonder what became of him and what he thought of the commercial postcards alluding to the haunting tale of the death of his mother and the well that claimed her life.

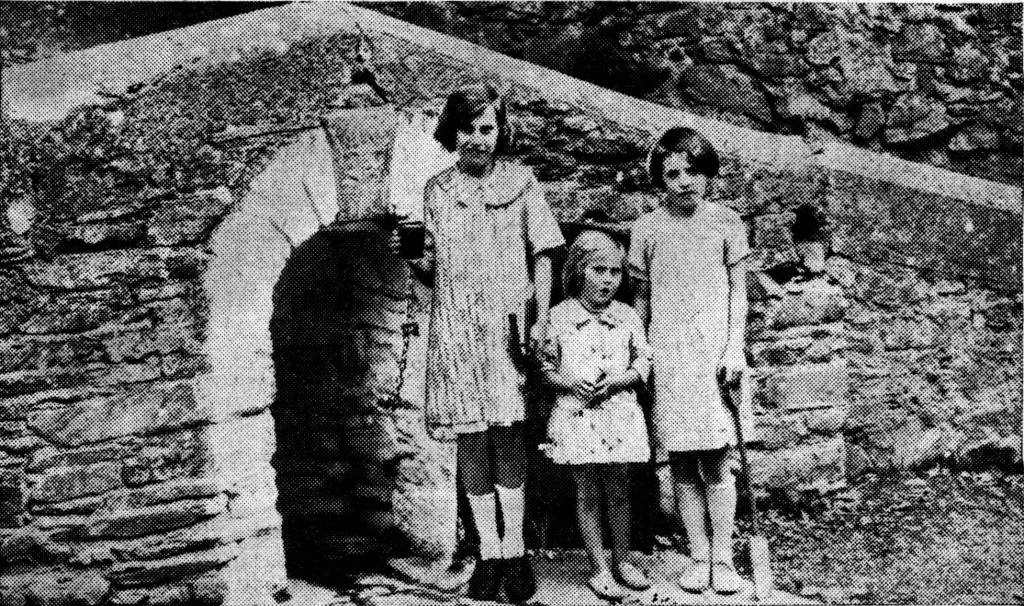

Certainly, by the year 1920 it was well known locally as ‘The Haunted Well’ and is referred to as such several times in the newspaper reports of a court case involving an assault that occurred there at that time. A photo of three young girls at the well was published in the Sunday Independent in October 1930, captioned: ‘At the Haunted Well — Tradition tells that at the mid hour of night spirits appear at this quaint old well at Tramore, Co. Waterford. It is known locally as ‘The Haunted Well’’.

The haunting of the well was recalled over the decades that followed, often mentioned in hushed tones on stormy nights. Witnesses recall hearing the dreadful screams of an old woman who could be glimpsed in the mist but disappeared on further investigation, invoking the mournful cry of the Banshee, a spectral entity reputed to manifest locally, particularly in Market Street, the Tank Field, Coolnacoppoge and Westtown. The Banshee serves as an omen of death, her chilling wail foretelling the demise of a relative. This belief has its roots in the ancient Irish custom of women keening for the deceased. She is often depicted as an old woman combing her long grey hair with a silver comb.

Certain accounts describe the Banshee as a washerwoman. The ‘Washerwoman’ was to be found at streams or wells, washing bloodied linen shrouds, preparing the garments for the burial of an unfortunate person shortly destined to die. Indeed, Mary Holohan herself is described as a laundress on her death certificate. Could she of become the catalyst for a new Banshee story in Tramore’s folklore? Or was the well considered to be haunted before her death? Your guess is as good as mine.

As for A H Poole, a man who did much to spread Tramore’s myths and folklore far and wide, he became a part of them in 1929 when he left a note for his family in their house on The Mall in Waterford saying that he was going to Tramore and was never seen again!

Ghosts from The Sea Horse

There are several eerie stories associated with The Sea Horse, a transport ship that was wrecked in Tramore Bay in January 1816 with appalling loss of life. There is an old legend that on wild stormy nights the soldier’s ghostly band of the 59th Regiment that were on board can be heard playing a tune called ‘Reel na Dhaibhche’ the meaning of which is ‘Song of the Sandhills’. Rev. Patrick Power, wrote about this in his book The Place-Names of Decies, that was published in 1907.4 It was reputed to be occasionally heard near the Rabbit Burrows, and on hearing the tune, local fishermen would draw in their lines and return home.

The story is also told of a skillful piper who listened to the tune and memorised it. When he played the music of the long dead band to a household in Tramore, the people within were so struck with fear that they never allowed the musician to darken their doors again. Nonetheless, the piper continued to play the tune until he was found dead on the strand one stormy morning, and it was put down to the vengeance of the ghost band of the 59th.5

A newspaper report in January 1917 stated that several people in Tramore had recently heard what was known as ‘the Banshee of The Sea Horse’, a sound resembling music. One witness stated that the uncanny noise kept him awake the whole night. The scientific explanation given at that time is almost as extraordinary as the popular superstition. The movement of the waves as they rush through Brownstown caves forms a natural notation in a minor key, which with the sea supplying the major key creates the illusion of music. This music of the elements or from the Otherworld, whichever view you like to take is heard as far inland as Knockboy and it is said to foretold ill tidings.6 One witness said that he grew up in the belief that the band played on stormy nights, and it would be hard to shake his convictions in the matter.7

Another ghostly account was chronicled in the regimental paper and subsequently published in an English newspaper many years later in 1885. Among those who tragically lost their lives on The Sea Horse was the wife of a sergeant, who had married without her parents’ consent. The father, who had never visited Tramore, experienced a profound dream in which his daughter appeared, imploring him to retrieve her remains, as she lay buried in a mass grave in the sand and could not find peace with a man’s arm draped across her chest. She revealed to him that he would discover her marriage certificate in her pocket. He travelled to Tramore, sharing the details of his quest with numerous individuals along the way, and a gathering of people followed him, eager to uncover the outcome of his endeavours. When he reached Tramore, he had the sand cleared from the exact location he had envisioned in his dream and there he found the body of his daughter with an unknown man’s arm draped across her chest and the marriage certificate in her pocket just as the dream foretold. The newspaper editor later responsible for disseminating the story insisted that he maintained a strict policy of publishing only those accounts that were substantiated by credible and verifiable evidence and testimony.8

In the tragic aftermath of the shipwreck, eighty two victims’ bodies were recovered and buried in Drumcannon Churchyard. However, the deteriorating condition of the bodies later washed ashore led to the creation of three large makeshift graves near the Rabbit Burrows where thirty-one bodies were buried.9 While over two hundred and fifty bodies were never found and were consigned to a watery grave. Over the years as human bones washed in on the strand from time to time, people would place them on the grave mounds, and the place became a site of horror with exposed human bones scattered along the crest of the strand. Considering the circumstances, it’s not surprising that people have always believed that the area is haunted!

Irish folklore is steeped in legends of phantom ships, often spotted navigating through dense mists in secluded bays before vanishing. The sightings are frequently dismissed as mere mirages or questions are raised as to the sobriety of the observers. In such narratives the phantom ship often serves as a harbingers of looming calamity at sea. In Tramore Bay, the phantom ship is described as having a brown sail, occasionally glimpsed through the fog by other vessels on stormy nights. The ship would appear as a warning to stay clear of the bay but would then take a toll; perhaps a spar or a piece of sail would be missed from the vessel in peril, as the phantom ship glided by.

Another tale recounts eerie sounds echoing on a tempestuous night at a strand near Westtown. Voices of men shouting and clamouring in foreign tongues were reported, with locals claiming that they were the spirits of the crew from a foreign ship that met its demise at the base of the cliffs long ago.

During the Great War, a remarkable event transpired when people were left astounded by a large fully rigged old style sailing ship that appeared late at night in a small bay in the locality of Kilfarrasy. The ship failed to respond when hailed by those on the shore. Out of apprehension and the obscurity of night, the onlookers resolved to delay their investigation until dawn. However, in the morning, the ship had vanished, leaving the country people firmly convinced they had encountered a phantom vessel, for it was inconceivable that such a large craft could navigate the shallow waters of that bay.10

The White Horse

In Irish mythology, white horses often appear in local legends, sometimes described as ghostly figures seen emerging from or disappearing into a river, lake or indeed the sea. In such circumstances the sight of a white horse was generally considered to be unlucky. In late November 1915, two well-known Tramore men, Fred Spencer and Jimmy Stubbs embarked on one of their customary nocturnal visits to the Rabbit Burrows, intending to set their snares to catch some rabbits. However, what was a tranquil moonlit calm was abruptly disrupted by an unfamiliar sound, echoing from a distance and rapidly drawing near. Alarmed by the ominous noise, they hastened to the edge of the sand dunes to discern its source. There, they beheld a huge white horse galloping fiercely across the sands. Initially paralyzed by fear, the men stood transfixed as the creature continued its frenetic charge towards the sea. Suddenly, both the horse and the sound vanished without a trace. Consumed by terror, the men fled the scene and hurried home. Yet, despite their trepidation, they resolved to return at dawn. Upon retracing their steps, they discovered no remnants of the horse or the mysterious figure—no hoofprints marred the undisturbed sand, even though the tide had not yet encroached upon the path forged by the animal. Confounded by this inexplicable encounter, they recounted their experience to several acquaintances, but no satisfactory explanation emerged.

In later years, their visits to the strand yielded no further sightings or sounds of the mysterious horse. This unsettling incident faded from their minds until years later when they found themselves at an establishment near the Halfway House, engaging in conversation about the Rabbit Burrows. They shared their extraordinary encounter there with Mrs. Power, the proprietor’s wife, who recalled her mother recounting a similar tale from long ago. She told them that a Coast Guard had been discovered dying at that very spot in days past, and with his last breaths managed to utter the words “The White Horse.”

There are other stories implicating corrupt coast officers in misleading sailors and their ships to wreck, which are frequently associated with the broader legend of Jack O’Lantern. In Tramore, Jack was reputed to be a man who carried a long pole with a lantern atop, tied to one of his legs. On particularly dark nights, he would pace the strand, creating the illusion of a harbour for vessels, beaconing numerous ships to their doom. He was ultimately exposed and executed, and now his ghost is said to now haunt the sands. Intriguingly, this tale has interwoven with the legend of the Guramooghagh to create a legend unique to Tramore.

To add another layer to the story, there are people who claim to have encountered the ghost of John Rogers, the Coast Officer, riding his white horse while patrolling the strand at night. Unfortunately, in all my research into 18th century Tramore, I’ve never come across a reference to the colour of his horse. Nonetheless, Rogers did not meet his end through violent means, but rather from natural causes, passing away of old age. His death was duly noted in the Waterford Mirror on 8 February 1813, “At Tramore, aged 95, Mr. John Rogers, for many years a Coast Officer of that district.”

The story of the white horse may be linked to the enigmatic disappearance of the renowned racehorse “Roar of the Ring” in 1905, that was believed to have found its final resting place in the Sandhills. The thoroughbred suffered from epizootic lymphangitis, a chronic and contagious fungal ailment, leading the Agricultural Department to issue orders for its destruction prior to it mysteriously vanishing. The horse’s owner, Mr. Fleming of Tramore, subsequently reported its disappearance to the authorities, but the horse was never found.

Fairy Rings, Haunted Roads and Headless Coachmen

Several townlands surrounding Tramore contain ringforts, or Liss, as they are referred to locally. These locations are often described as fairy rings and linked to ghost stories and the folklore of the fairies. Throughout Ireland, it is deemed extremely unlucky to plough or damage a Liss in any manner. One notable Liss at Coolnacoppoge is recognised for its peculiar phenomena. Situated just off the road to Fenor, this particular Liss was believed to be sacred to fairies, and no mortal was permitted to cut down a tree or remove a stone from its vicinity. Children living nearby were cautioned to avoid entering, lest they be taken by the fairies. Few would dare to walk through it, and many locals believed the road adjacent to it was haunted.

One account recalls a man riding his bike home late at night, who discovered a comb on the roadside. As he reached down to retrieve it, he encountered the Banshee and heard her mournful wails. In his fright, he abandoned his bike and fled home, only to find it at the back door upon his arrival. A woman who worked nearby described walking along the same stretch of road when she halted to tie her shoe. Glancing between her legs, she saw two hooves and ran away in terror. The following day, she returned with others to inspect the area, and discovered two hoofprints in the mud at the precise location where she had stopped.

Others recount hearing stories from their parents regarding the gates that never stayed closed, but opened for the headless coachman to pass through. The headless coachman, or headless horseman known throughout Ireland as ‘The Dullahan,’ was frequently sighted and heard all around the parish of Dunhill and Fenor. The ghostly coach traversed the roads from Reisk by way of Ballydermody, Fenor, Islandtarsney, Coolnacoppoge and onward to Tramore. Locals would flee upon hearing the sound of hooves at night, fearing the approach of the headless coach. Of course there were more worldly reasons to fear the sound of horses at night in rural Waterford, the militia or the constabulary could be on patrol.

Additionally, on the opposite side of Tramore, at the horseshoe bend on the Ballynattin Road, strange occurrences were said to unfold at night, instilling fear in both men and horses as they passed by. Horses had been known to sweat in terror and refuse to move, even under the spur of a whip. The Sheevra, a diminutive figure who lived there long ago, was widely regarded as a fairy changeling. He possessed extensive knowledge of herbal remedies and dedicating his life to offering cures and interpreting people’s dreams. He was believed to hold remarkable powers, resulting in the priests of that time forbidding the populace from seeking his assistance.

As we travel a little further from Tramore, we encounter legends in every townland. Thus, a multitude of ghostly tales persist from the past, that once echoed through generations around the hearths of the people, recounted at night while the wind howled in from the raging sea on dark October nights.

- Waterford News, 12 July 1901. ↩︎

- Edmund Downey, A Guide to Tramore and its Neighbourhood, Waterford 1919, page 21. ↩︎

- The Irish Independent, 20 June 1911. ↩︎

- Rev. Patrick Power, The Place-Names of Decies, London 1907, page 370. ↩︎

- Cork Examiner, 20 September 1929. ↩︎

- Kilkenny Moderator, 24 January 1917. ↩︎

- Munster Express, 24 December 1930. ↩︎

- Manchester Courier, 24 September 1885. ↩︎

- The Drumcannon Parish Register, Representative Church Body Library. ↩︎

- Cork Examiner, 20 September 1929. ↩︎

Leave a comment