In the early 18th century, most roads in Ireland were little more than trackways carved by the movement of carts and wagons over the centuries. There’s an old story that was first published in A Guide to Tramore in 1854 concerning the old rutty and stony road that led from Waterford to Tramore in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, that goes like this. The vehicles of transportation in those days were jaunting cars or truckles, which consisted of a simple framework of timber, mounted on block wheels. The ladies generally went in the cabs, while the men rode on horseback, as it was considered effeminate for a man to appear in any kind of vehicle. According to the guide, the first vehicle that attempted to run between Tramore and Waterford was an inside car driven by a man named Edmund Phelan, better known as Ned Foe. Ned was described as an original character, full of the legendry lore of the district, with which he entertained his company on the journey. Ned was soon joined by another carman named Eammon an Amhran, Ned of the songs, ‘a hearty, jovial and disposed fellow’. These men continued their occupations for years, working in concert, helping each other in case of attack, breakdown, or fights at the Halfway House. Back then, the road was in a dangerous state, full of large holes and they sometimes brought bags of gravel from the strand to deposit in the holes and erected landmarks on the hedges, to signal the most dangerous areas.1

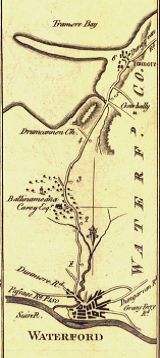

The reality is far more nuanced. The road from Waterford to Tramore first appears on a map in Charles Smith’s History of Waterford, published in 1746. This heavily stylised map shows a road running from Waterford to Tramore and another from Tramore to Dungarvan.2 Interestingly, all the roads are depicted as running straight, whereas most were almost certainly meandering routes that evolved from medieval dirt tracks. Although while some roads were originally made for the use of the military, the Tramore Road was not one of them. Moreover, as passenger vehicles became more popular, new roads with gentler slopes were made for their use which followed the curvature of the land. By the mid eighteenth century, Irish roads were cheaply made and repaired with layers of earth, gravel and broken stones and often flanked by drainage ditches.

A more accurate depiction of part of the route from Waterford to Tramore appears in Richards and Scale’s Plan of the City and Environs of Waterford published in 1764 which shows the road leaving Waterford at John’s Hill and running through Ballynamona. At this time Tramore had several public houses and was regularly visited by gentry from the city, but the journey could be hazardous as poor Barry Gardiner found out on 19 August 1766. He was returning from Tramore, where he had been to ‘take the air upon the Strand’, when he fell from his horse, and broke his neck.3

Travel Guides

The road was considered important enough to be included in George Taylor and Andrew Skinner’s Maps of the Roads of Ireland, surveyed in 1777. Their policy was to survey all roads that were fit for substantial wheeled vehicles. This simple map shows the road running from John’s Hill, over Ballytruckle, Kilcoghan, Ballinamona, Ballykinsella and Drumcannon, descending at Ballynattin, before rising again over the hill of Garrancrobally, and entering Tramore itself. The road ran down the hill with buildings on both sides as far as the strand.4

The first edition of the Post Chaise Companion, or Traveller’s Directory Through Ireland, published in 1784 contains a short entry detailing the road from Waterford to Tramore. A post-chaise was a fast carriage of a practical design suitable for delivering post and two to four passengers. It usually had an enclosed body mounted on four wheels and was drawn by a team of two or four horses. They were hired with a driver and horses for fast long-distance travel. At each posting station, a new driver and team of horses would take over and the original driver would return to his station. The road was described as six miles long, and it was further noted that, ‘Two miles and a half from Waterford on the left is Ballynamona, the beautiful seat, with large demesnes of Mr Carew. Drumcannon Church stands at the foot of a high hill, about a quarter of a mile from the road, on the left within two miles of Tramore.’5 The 1786 edition has much more to say’ describing Tramore as being ‘deservedly considered the Baiae of the eastern coast of Ireland’, being ‘situated on the declivity of a very steep hill that gradually sinks into a beautiful strand’. The town was described as having formerly consisted chiefly of fishermen’s huts that were built in a scattered irregular manner but was ‘daily improving’ under the proprietorship of Bartholomew Rivers, who was credited as having built ‘several small edifices with a handsome market house, assembly room & C.’ at his own expense and as having ‘diffused a laudable sense of industry among the inhabitants’. The guide went on to mention that it was ‘much frequented in the summer season for the benefit of sea bathing by the neighbouring gentry’.

In a good day, with a car and pair of horses, you could journey from Kilkenny to the Ferry Slip, across the ferry to Waterford Quay, and onto Tramore. Moreover, with the completion of Waterford Bridge in 1794, the journey became much more convenient. Alexander Taylor’s Traveller’s Guide to Ireland, published in 1794, noted that ‘Tramore is much frequented as a very pleasant summer bathing place; it is in the estate of Lord Doneraile and has an extensive and commodious hotel and a number of excellent houses built principally by Mr Rivers, one of the bankers of Waterford.’ It noted that Tramore was 82 miles, 1 furlong from Dublin and 6 miles from Waterford.6

William Wenman Seward’s Topographia Hibernica was published in 1795. In it he stated that there were fairs held in Tramore on the 3 May, 25 July, 1 October, and November. He continued, ‘Tramore is much frequented as a very pleasant summer bathing place and is considered as the Baiae of the eastern coast of Ireland. It has been much improved by its present proprietor Bartholomew Rivers, Esq, who has erected a handsome market house and assembly room there.’ He was seemingly unaware of Rivers’ bankruptcy in 1793. The book also mentions Duaghmore, an island situated near Tramore Bay, County Waterford, casting considerable doubt as to whether the author ever set foot in the vicinity. Matthew Sleater’s Introductory Essay to a New System of Civil and Ecclesiastical Topography, published in 1806 merely repeats the entries in the previous guides, adding nothing new on the subject of Tramore while Nicholas Carlisle’s A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, published in 1810, also repeats most of the information of the other guides verbatim and only adds that the village had six post days a week, implying that a coach ran a regular daily service to and from Waterford city excluding Sundays.7 A later 1819 guide informs us that a letter from Dublin cost a postage of 9d.

The Roads West

The map in Charles Smith’s History of Waterford, also shows a road running from Tramore to Dungarvan. The road leading from Tramore to Dungarvan is also marked in George Taylor and Andrew Skinner’s Maps of the Roads of Ireland, surveyed in 1777. The first edition of the Post Chaise Companion, published in 1784 accompanying map of the country’s road network does not include the Tramore Dungarvan Road. An 1802 map of the Earl of Enniskillen’s estate in county Waterford shows the road leading west from Tramore running through Coolnacoppogue, Islandtarsney, Ballyscanlan, Fenor and onwards to Dunhill, with a branch road leading to Annstown. Another road is partially shown running from Islandikane through Garrarus and Westtown which presumably joined with the main road at Newtown.8 The Traveller’s New Guide Through Ireland 1815 described ‘From Tramore a road sweeps off on the right, running along the coast to Dungarvan, on which road many fishing villages, and hamlets are situated, but no place, or town of consequence sufficiently remarkable to attract the traveller’s notice’.9

Commercial Coaches

By the summer of 1807, we learn that the Waterford to Tramore coach known as the ‘Sociable’ final stop was outside of Coghlan’s Hotel. From 25 June, the carriage set out from the Commercial Hotel during the season, every morning at 7am to arrive at Coghlan’s at 8.30am. The coach then returned at 10am to arrive in Waterford at 11.30 am. The afternoon coach left Waterford at 3pm and arrived at 4.30pm. and returned at 7.30pm. Places were to be taken at the bar, for six inside passengers at 1s 8d each and one outside passenger at the lesser rate of 1s 1d. Places would not be kept if the money was not paid at the time of booking.10 The cost of these vehicles was considerable. In August 1813 an inside car, as good as new with harness was offered to be sold for 40 Guineas and an outside car of the newest construction for 20 Guineas, as advertised in the Freeman’s Journal.11 Nonetheless, many businessmen were tempted to invest in public transportation.

One of the first known entrepreneurs to run a coaching business on the Tramore Road was Thomas White, who advertised cheap travelling to and from Dunmore and Tramore in a notice dated 12 May 1816. He stated that due to the encouragement that he experienced the previous Summer in running his jaunting cars on the Tramore Road that he now intended to run two jaunting cars, an inside and an outside between the city and both those places every day during the ensuing season, commencing on Sunday 19 May and so arranged that one of them would stop in each place every night. The Tramore cars would set out from Waterford at 8am and 6pm and would also leave Tramore at the same hours. The strictest regularity would be observed in dispatching the cars at those hours and the utmost attention would be paid to the safety and convenience of the passengers. Fares were advertised as 1s 8d single and 2s 6d return. Places for Tramore would be taken at Mr Francis Carigan’s, Broad Street.12

By 1822, the famous Charles Bianconi was running a Tramore car from the Bush Tavern in Kilkenny every morning during the summer months. The car left at 6am and arrived in Tramore at 12.30 pm. It then left at 1pm and arrived at the Bush at 8.15 pm on the same day. Fares were advertised as 6s 11d. It was particularly requested that any complaints against persons connected with the establishment would be immediately made directly to Bianconi in Clonmel. Bianconi was running well appointed day cars that carried passengers and parcels and travelled from five to six miles an hour with good horses and careful drivers, one of which was a fellow named Phelan.13

Crime on the Road

In September 1823 mention was made in both the Irish and English newspapers of ‘the outrageous conduct of some of the fellows who plied their jaunting cars between Waterford and Tramore.’ It was reported that some of the drivers caused a ‘shocking accident’ due to a ‘scandalous competition’ between them ‘which nearly proved fatal to a respected fellow citizen’. Mr. William White of King Street was returning to town on one of those vehicles. He was near the bottom of Ballytruckle Hill when he was thrown upon the road in a race between the car upon which he sat and others. The shaft of the succeeding car struck him violently in the chest or side, broke one or two of his ribs, knocked him down and the wheel passed over one of his legs fracturing it near the knee. Notwithstanding these severe injuries Mister White was going on as favourably as could be expected under the circumstances.14

Although popular, the road was often a lawless place, the scene of excessive drinking, gaming tables, prostitution, highway robbery and child abandonment. On Wednesday evening 26 June 1793 as three of the Misters Strangman of Waterford City were returning from Tramore they were stopped about a mile from town by two footpads with their faces blackened who robbed two of the gentlemen of their watches, one guinea in gold and a few shillings. Two men were arrested on the following night and committed to jail on suspicion of having committed the robbery.15 In another incident reported in November 1806, a young girl by the name of Walsh who had been selling milk in the city was abducted on the Tramore Road. The assailant was caught and lodged in prison:

Waterford 10 November 1806. On the evening of Sunday last, one of those outrages was committed in our neighbourhood which so often brought down the last severities of the law upon the perpetrators, but which, fortunately for the peace of society, are now less frequently committed: -a young girl of the name of Walsh, who had been selling milk in the city, was seized on her return home by a person named Russell, aided by some associates, and forcibly put into a carriage. The transaction took place on the Tramore road, which they immediately quitted, took the Dunmore Road, and drove directly to the house of Mr Power, a respectable farmer. Mr Power, highly to his honour, instead of promoting the designs of the infatuated young man, ordered him to leave his house, afforded the girl complete protection, and restored her next morning to her friends. Russell has since been apprehended and lodged in prison. The circumstances of this case are likely, we understand, to admit of an accommodation between the parties; but we cannot help stating, that the offence is one of the most criminal in nature, and that the law has adjudged it to be a capital punishment. The lower classes of society may in some cases be ignorant of the law; but they can and in no case be ignorant, that every encroachment on the rights and liberty of another is criminal – the violation of moral and religious duty; and the little reflection would, on every occasion, convince them, that the indulgence of guilty passions can never be suffered to pass with impunity in a civilized country.16

Ten years later, in December 1816, a Waterford newspaper reported that ‘about 9 o’clock on the night of Saturday last as William Ronayne Esq of Balindud was returning home from this city, he was summoned to stop near Kilcohan about two miles distant and on the Tramore road. The party consisted of two or three armed men. Mr. Ronayne paid no attention to the demand but proceeded at a rapid rate. One of the assailants fired but without effect and Mr. Ronayne reached his home in safety.17 Another incident of lawlessness occurred on 6 February 1827, when a fellow named Denis Bryan committed highway robbery on the Tramore road. He appeared before the City Court the following month, when an unsuccessful attempt was made to prove an alibi. The learned judge, ‘in an impressive manner’, pronounced the sentence of death against the prisoner; but held out a distant hope that the sentence might be commuted to transportation for life.18 On Saturday morning 14 April 1827, the corpse of a girl about six weeks old was found in a field beside the Tramore road, just at the city side of the two milestone. Alderman Henry Alcock of Waterford, magistrate for the county, held an inquest. The verdict was that the child came to her death in consequence of being exposed to the inclemency of the weather.19 On 10 July 1827 a carman named Nicholas Powell was fined 10 shillings by the mayor for leaving two jaunting cars on the Tramore road without any person in charge. A child was badly hurt by the wheel of one of the cars running over its foot.20

The Waterford Mirror, 22 March 1828, reported that Thomas Byrne was indicted in the city court for stealing money from John Morrison. From the statement of the prosecutor, it appeared that Byrne had a gaming table on the Tramore road near the Leper House wall. The incident occurred on 10 March when Morrison was tempted to try his luck at the game, but having lost 7s 6d and suspecting foul play, he challenged Byrne with it and laid hold of him, when Byrne darted his hand into Morrison’s pocket in which was 25s in silver and drew out the greater part of it. Morrison caught his hand, but unfortunately some of the money fell on the ground which he picked up but about 12s was taken by Byrne. Four of Byrne’s companions attempted to rescue him but failed. Byrne produced no witness and was found guilty and sentenced to be imprisoned for six months.21

In August 1833, the Waterford Mirror reported on an inquest was held by Alderman Evelyn, the coroner upon the body of an old woman named Ryan who was run over by a jingle on the previous Monday evening upon the Tramore road. After hearing the testimony of witnesses of the sad occurrence, the jury returned a verdict that the deceased came by her death in consequence of being run over by a jaunting car which was ‘driven furiously and negligently’ by John Matthews, him being at the time in a state of intoxication. It was further noted that Matthews had absconded.22

Two years later, a Mr John Daniel appeared at the petty sessions to complain of an assault committed on him by James Phelan, a Tramore car man. It appeared that Mister Daniel took a journey in Phelan’s car from Tramore to Waterford. When Daniel went to pay the customary fare of 6d, Phelan not only refused to accept less than 8d but collared Daniel and shook him. Mr. Daniel then asked for the number of the car, which Phelan refused to give. They then searched for Mr Wright, possibly the city jailer, to resolve the conflict but failed to find him. Phelan then threatened Daniel, saying that he would take him back to Tramore, and on the way, would make him pay what he demanded. Terrified at the threat, Mr Daniel attempted to get out of the car when he was severely hurt. Instead of Phelan assisting him, he again collared him and repeated his threats. At length Mr. Wright was found, and he advised Daniel to prosecute. The Judge declared that Mister Daniel deserved a great deal of credit for the way he acted in bringing the matter before the public and after admonishing the carman on the impropriety of his conduct fined him £1 or a month’s imprisonment. The newspaper report on the incident was published under the headline, A Caution to Car Drivers.23

A ‘Diabolical Outrage and Murder’ occurred on Thursday January 1836, when a woman named Mary Mullowney from the barony of Iverk, in the County Kilkenny attended the funeral of one of her neighbours who was interred at Tramore on that day. On returning home in the evening accompanied by four men – also her neighbors, they tied a handkerchief tightly around her neck to prevent her crying out and then violated her person. The woman was found dead the next morning between the forge on the Tramore Road and the turn to Drumcannon churchyard. ‘The woman was no doubt strangled by those demons in human shape after affecting their wicked purpose, in order if possible, to evade the consequence of their hellish deed’. The Waterford Chronicle reported that an inquest was being held on the body and that the guilty parties had been identified.24

The Turnpike Proposal

A writer in the Waterford Mail, 28 June 1828, remarked that the Tramore Road was an important and much traveled line of communication but was invariably kept in a disgraceful state. It appeared to be so totally neglected that it would soon be next to impassable. There were gaping holes in the road that were daily increasing in size and urgently needed to be filled up. The article continued: ‘Tramore as a bathing place is perhaps the very first in Ireland. For purposes purely salutary it has always had the preference from medical men and, of late, it is so much enlarged and has so many comfortable as well as elegantly furnished lodgings at the most reasonable prices that it is equally desirable as a place of amusement or of health. We have a right therefore on behalf of the public to require that the high road leading to such a bathing place and considerable town, shall not be permitted to grow as rugged and as disagreeable as some wretched bye lane leading to nothing, but that it shall be kept at last in passable repair. We trust this little notice may meet with early attention, and more particularly as the longer the necessary repairs are deferred, the greater will be the public inconvenience and eventual expense.’25

The proposed solution to the state of the Tramore road was to introduce a tax in the form of a toll, known as a turnpike. Before 1700 the responsibility for the upkeep of roads had been local, with individual parishes being charged for annual repairs. However, the introduction of the turnpike system on certain roads transferred the charge from local parishioners to road users. A toll was levied on non-local traffic which was then used for the maintenance of the road. Turnpike trusts were formed to undertake responsibility for the administration of the system. On 10 April 1829, a resolution was put forward to establish turnpikes on both the Dunmore and Tramore roads at a meeting of the members of the Turnpike Board held at Dungarvan. Whether intentionally or by some oversight, no opposition was presented to the projects by the county and city grand juries and the resolution was passed. The board then submitted it to the committee of the House of Commons, where it was about to be pressed forward into law. When this news came to light, a committee was appointed to devise the best means of preventing the proposed erection of turnpike gates on the roads. A public meeting was held on Tuesday, 28 April at the town hall with the mayor presiding, to take into consideration the report of the committee. Mr. Mortimer of the Turnpike Trust stated that the roads were very expensive but badly maintained and that under the management of the trust, the roads would be kept in better repair at less expense. He therefore proposed that the resolution go before the committee of the House of Commons, without note or comment, leaving it to their wisdom to decide the best course of action.26

However, the general feeling of the jury was that as a considerable portion of the expense of maintaining the Tramore road fell upon the city, and it was principally used by the citizens in their excursions to the principal bathing place in their neighbourhood it would be ungracious to press the erection of a turnpike gate upon that road. Furthermore, no benefit would result to the immediate neighbourhood of Tramore from the establishment of turnpike gates and the road would be used far less and result in great injury being afflicted on the owners and occupiers of the lands and houses adjacent to the line. Others noted the severe pressure which the establishment of Turnpike roads would inflict on all who had occasion to use the roads, particularly the poor proprietors of the numerous vehicles which plied on them for hire.

Councillor Hayes stated that the expenditure on the maintenance of the roads was ill managed. At times when the Tramore road was in a shamefully neglected state, the county and city grand juries totally disregarded the strong advice given to them and although Mr. Christmas offered to undertake the superintendence of the repairs of the road at 10d. per perch they actually voted 1s. per perch to Mr. Thomas Carew who was notoriously one of the worst persons that could be found to execute such a task and that the repairs done under his superintendence were executed in the most slovenly inefficient and unskilful manner. Mr. Hayes further noted that a new line of road to Tramore was in contemplation. After much discussion, it was then agreed for the committee to prepare a petition for parliament calling for the omission of the clauses relative to the two roads contained in the proposed bill.27

The following year at the Spring Assizes, William Walsh was appointed contractor for keeping in repair 806 perches of the road from Waterford to Tramore, from the Leper Hospital to the Three Milestone, at 8d. per perch, for seven years. However, an article in The Waterford Chronicle that summer, entitled ‘The Road to Tramore’, informs us that the road was still in a horrible state and Lord George Beresford was requested to investigate it and have a presentment passed to repair it at the next assizes. The newspaper writer then added that the gentleman in Tramore, who stood indebted to the newspaper for a small sum for postage, would ‘expend that sum in filling up a large hole midway between Tramore and Waterford. He cannot mistake the spot, as it exhibits a miniature representation of the mouth of a Welsh coal pit.’28

A New Road

In May 1830, the Waterford landowner Lane Fox arrived in Waterford City on a visit to his large estate. From there he went to Tramore in company with Thomas Wyse for the purpose of viewing the countryside, preparatory to forming a new line of road and a canal between both places.29 Further impetus to such a project arrived in 1831, when the Board of Works was established by an act of parliament entitled ‘An Act for the Extension and Promotion of Public Works in Ireland’. Sensing an opportunity for state investment, an editorial in the Waterford Mail stated that:

‘We know of no public work which would come more entirely within the spirit of the act lately introduced by the government than the draining of the lands of Kilbarry, in our vicinity, and the making of a new road to Tramore by that line. Both works either considered separately or together, would be an immense public advantage. Many spirited individuals were ready to cooperate, promote the work, and to subscribe liberally towards it, if a few gentlemen of influence and property would step forward and take the lead.’30

It was argued that it was the right time to provide ample employment after the harvest and there were no serious obstacles preventing a fast start to the work. A great deal of the preliminary labour had already been done, the land having been surveyed and mapped.

Furthermore, the line of the road had been marked out and measured, and estimates had been formed of the expense.31 The map in question was entitled ‘A Map of the Road from Waterford to Tramore with Proposed Improvements by Thomas Kearney 1831.’32 The plan of the road was discussed a good deal by the grand jury of the county at the last assizes to general approval. The immediate funds would be supplied by private subscriptions and a loan from the commissioners under the act. The work combined several benefits. The new road would run upon a dead level and would shorten the distance to Tramore by a mile and a half. Instead of ‘toiling over the frightful hills’ on the present road for nearly an hour and a half, the journey on the new road could be made ‘with perfect ease in three quarters of an hour’. It was estimated that the increased proximity of Waterford would add thirty percent to the value of houses in Tramore. Moreover, not only would the drainage of Kilbarry, which would go hand in hand with the making of the road, add greatly to the healthfulness of the city by removing the extensive marsh in its immediate vicinity, but it would also lead to several hundred acres of the richest farmland being reclaimed. Another article in the Waterford Chronicle published in the following month reads:

‘This road reminds us of what Swift said of the houses in Ireland-‘ that they were all built near good situations,’ for although the road runs over as many hills as are to be found on any six mile line of road in Ireland, had there been placed but one hundred yards at either side, it would run on a dead level, and shorten the distance at least a mile. We are aware that several public meetings have taken place with a view to remedy the evil by getting a new line of road, but as this mode of proceeding has been ineffectual, we hope that some person will procure a presentment for it at assizes. The grand jury will scarcely hesitate to grant the presentment for a work of such general convenience and utility’.33

On 21 March 1832, the Clonmel Herald published a notice that the grand juries of the county and city of Waterford had presented for a new road to Tramore to leave the Cork road at the Kilbarry churchyard, and to enter Tramore opposite the Strand Inn. This was said to be the longer of the two lines laid before the grand juries. A further sum of between two and three hundred pounds was estimated as the expense of draining the notorious bog of Kilbarry. It was understood that permission for building the road was granted only on condition of the marsh being drained.34 In April 1834, the Waterford Mail reported that the construction of the city portion of the new road was about to commence immediately and that parallel to the line of road a canal was to be excavated from the pill in the Manor, and through the lands of Holy Ghost hospital and Mr Fox, to Sheep’s Bridge, a distance of two miles from town. The canal would be navigable by small boats. A great number of men were already at work, but they thought that 10d a day was too little for the severe labour they had to endure.35

A few months later, the Waterford Mirror reported that on a Monday Morning, the body of a female child, only a few days old was found in a small hamper in the new canal. Some marks of violence apparently inflicted before it was thrown into the water were discovered on the body. Alderman Evelyn, coroner, held an inquest when Dr Briscoe having examined as to the cause of its death, a verdict was returned that the child had come to its death by foul means, the perpetrators of which were unknown.36 Again on Thursday morning, 21 June 1838, the bodies of two infants were found floating in the canal at the side of the new Tramore road. An inquest was held at the town hall, before Alderman Evelyn on the bodies, when a verdict of found dead was returned. No clue had been obtained as to the perpetrators of what were described as ‘unnatural deeds’.37

The fourth day of the Tramore races was known as ‘the great St. Ledger day,’ which was very popular as a steeplechase was held. The ground marked for the chase ran parallel with the mile of the new Waterford road next to Tramore. The starting post was two or three fields from the strand and the turning post was near the junction of the new road with the old. From the newspapers we learn that preparation had been in progress from the early hours of the day and that the principal roads to Tramore were occupied by countless throngs of people and as the appointed hour approached more closely, it became scarcely passible without great difficulty. As the starting time drew near, the hills, which surrounded the course like an amphitheatre, were teeming with spectators, while the immediate vicinity of the course was densely crowded with anxious spectators.38

A surveyor’s report from July 1936 stated that the road was on the eve of completion. It was noted that the road was granted on the express understanding that the drainage of Kilbarry would be undertaken at the same time.39 Two months later, the road appears to have been in fully working order, as the Waterford Mail, reported that following several complaints that the entrance to Strand Street from the new road was obstructed by horses and cars on Sundays, an order was issued to the police by Mr Pierce George Baron to keep the passage free; and to have the cars resume their old station. The newspaper writer anticipated that the regulation would add much to the comfort and security of passengers.40

Meanwhile, the old road was still in use and dangerous as ever. On a Monday evening in October 1836, a farmer named Thomas Murphy living at Killowen was thrown from his horse while riding down the hill leading from Drumcannon. He was so dreadfully fractured in the skull that he survived the accident but two hours. He left a wife and children to deplore his loss. On the following Wednesday evening, a farmer named McGrath from Ballygunner was run down by some persons riding home from the races near the halfway house on the Tramore road and so severely injured that he died on the next evening.41

In June 1837 the contractor for the county part of the Tramore road wrote to the editor of the Waterford Chronicle: Having observed in your last two papers observations on the dangerous state of the new road to Tramore, and having all due respect for the opinions of your enlightened journal, I request to be informed what part of said road you consider dangerous and disgraceful, as I have not been able to make the discovery, though I have carefully inspected the road for the purpose. The newspaper editor replied that, ‘it would be difficult to name one part of the new road more than another which deserves the above appellation, if we excect a few miles of it near the city and some perches near Tramore. A quantity of stones thrown together renders it almost impassible for cars or horses. Should traveling, however, be continued on it, perhaps the cause of complaint would be considerably abated. In all other respects the road is a good one, broad and well made and promises to do credit to the maker.42

The following month, the same newspaper was able to report that the new road was getting into fine order, affording a six-mile drive without a single hill to disturb the enjoyment of those travelling to Tramore. It was also announced that a road (The Upper Branch Road) was also to be cut between the present new road and Green’s Lane (Queen Street) which would be of a great convenience to lodgers in the upper part of town. The storm wall was reported to be progressing rapidly, a project that also entailed extending Strand Street from the Ladies to the Men’s Bathing Places.43 It was at this time that William O’Neil named his premises ‘The New Road Hotel’.44 This business was subsequently to become the Hibernian Hotel.

Unfortunately, as the new road became more popular, the old road was allowed to fall into a state of disrepair and in September 1837 it was reported to have become nearly impassable. The ruts in the road were deep and not more than a few yards apart. ‘Persons desirous of experiencing an excellent jolting and running the risk of breaking their legs would do well to go on it without delay.’45 An insight into the type of vehicles on the road at this time can be gleamed from a July 1839 advertisement in the Waterford Mail for a splendid new Dublin built outside car of the best construction, never used, for sale at 33 Guineas, along with an excellent Swiss carriage to be sold cheap. Both carriages could be seen at Mrs Phelan’s Hotel, Tramore.46

At the city presentment sessions in June 1841, the application from the contractor on the new Tramore road was rejected in consequence of the surveyor stating that he could not certify that the road was in a state of repair.47 The following year, the Waterford Chronicle called people’s attention to the exposed and unwalled condition of the Tramore road and asked if would take a justice of the peace to be drowned in it before it was fenced as ‘surely no one in his senses would think of fencing a place after the drowning of a poor Carman and his horse’.48 The old road still had its uses beyond local access as during the floods of the winter of 1852, which were particularly hard on the new road. The jingles were axle deep on the road during the race days and in fact for three or four weeks nearly all the traffic to and from Tramore transferred from the new to the old Tramore road.49

The official opening ceremony of the Waterford and Tramore Railway took place on 5 September 1853. It was to be a most significant date in the development of the town, but perhaps not such a watershed as it is sometimes made out to be. A Guide to Tramore in the following year, described the new road and it’s cars as such, ‘Such was the mode of travelling on the old road, but improvements began, M’Adam appeared, a new road was made level, smooth and well kept…, good cars were then built for the road, and their numbers increased till they amounted to more than 200 and the journey was made to less than an hour.’50 However, the coming of the railway had a devastating affect on the jaunting car trade. A public meeting of the proprietors of houses and property in Tramore was held in the Grand Hotel on 3 April 1859, in reaction to comments made by Sir James Dombrain of the Railway Company, stating that there was no proper winter accommodation at Tramore. The general opinion at the meeting was that there were more unoccupied houses in Tramore during that winter than in living memory. The mismanagement of the railway company not only drove away many respectable previous residents from the town during the winter months but prevented others from coming to reside who formally found inducements in getting a superior class of house at a mere nominal rent. John Waters Maher stated that since the year 1845 he had not seen Tramore so deserted as during that winter; even in the times of the old cars he generally had six or seven houses occupied in winter, but now that the cars were gone, the railway company had a perfect monopoly and limited winter train coverage.51

- Partially reprinted in The Waterford News, 22 December 1894. ↩︎

- Charles Smith, The antient and present state of the county and city of Waterford. Dublin 1746. ↩︎

- The Dublin Journal, 19 August 1766. ↩︎

- Taylor and Skinner, Maps of the Roads of Ireland, London 1778, page 164. ↩︎

- W Wilson, Post Chaise Companion, or Traveller’s Directory Through Ireland, Dublin 1884, page 218. ↩︎

- Alexander Taylor, Traveller’s Guide to Ireland, Dublin 1794, pages 66-68. ↩︎

- Matthew Sleater, Introductory essay to a new system of civil and ecclesiastical topography, 1806; Nicholas Carlisle, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, London 1810. ↩︎

- William Larkin, A Map of the Estate of the Right Honourable the Earl of Enniskillen in the County of Waterford, 1802. ↩︎

- John Cunning, The Traveller’s New Guide Through Ireland, Dublin 1815, page 210. ↩︎

- The Waterford Mirror, 24 June 1807. ↩︎

- Freeman’s Journal, 30 August 1813. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 16 May 1816. ↩︎

- Finn’s Leinster Journal, 24 August 1822. ↩︎

- John Bull, 29 September 1823. ↩︎

- Waterford Herald, 29 June 1793. ↩︎

- Belfast Chronicle, 15 November 1806. ↩︎

- Freeman’s Journal, 19 December 1816. ↩︎

- Tipperary Free Press, 21 March 1827. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 18 April 1827. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 11 July 1827. ↩︎

- The Waterford Mirror, 22 March 1828. ↩︎

- Freeman’s Journal, 14 August 1833. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 20 June 1835. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 23 January 1836. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 28 June 1828. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 2 May 1829. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 2 May 1829. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 31 July 1830. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 19 May 1830. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 6 August 1831. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 6 August 1831. ↩︎

- Road: Waterford to Tramore, National Archives of Ireland, OPW/5HC/6/430A. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 17 September 1831. ↩︎

- Clonmel Hearld, 21 March 1832. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 9 April 1834. ↩︎

- The Pilot, 19 September 1834. ↩︎

- The Waterford Mail, 23 June 1838. ↩︎

- Kilkenny Moderator, 21 October 1835. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 13 July 1836. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 7 September 1836. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 1 October 1836. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 24 June 1837. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 22 July 1837. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 7 October 1838. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 30 September 1837. ↩︎

- Waterford Mail, 20 July 1839. ↩︎

- Waterford chronicle, 12 June 1841. ↩︎

- Waterford News, 31 May 1850. ↩︎

- Waterford News, 24 December 1852. ↩︎

- Partially reprinted in The Waterford News, 22 December 1894. ↩︎

- Waterford Chronicle, 9 April 1859. ↩︎

Leave a comment