Seawater bath houses have a long history in Ireland. The therapeutic use of seawater for health and wellness purposes has been practiced for centuries in various cultures around the world, including Ireland. However, it wasn’t until the 18th and 19th centuries that seawater bath houses became popular in the country. The high mineral content of seawater was thought to have a positive effect on skin conditions, respiratory ailments, and rheumatic disorders. People would often visit these bath houses for treatments, relaxation, and general well-being.

The Tramore seawater baths were established in the early 19th century and played an important part of the town’s visitor industry, attracting both locals and visitors eager to experience the supposed health benefits of seawater. However, not everyone found a visit to the baths to be beneficial. The Waterford Mail, 25 August 1832, reported that, ‘a young man from the Queens County, after a hot bath at Tramore, on Tuesday last, lay in a field and fell asleep. On his waking, he found himself reduced to such a state of debility that he immediately retired to bed and became so alarmingly indisposed that medical assistance was immediately called in, but every exertion made for his recovery proved unavailing as he died a few hours afterwards.’

This tragic incident raised questions about the safety and efficacy of the baths. Despite such negative reports, the bath houses continued to flourish, as many patrons believed in the therapeutic properties of the seawater, providing a sense of solace and rejuvenation amid the picturesque coastal scenery, which was a key factor in the continued popularity of Tramore as a seaside resort destination.

William Hill, who served as the agent for Lord Doneraile in Tramore, took to the pages of the Waterford Mail on 23 February 1833 to announce an appealing opportunity for prospective tenants. The advertisement highlighted that the baths and additional premises, formerly occupied by a Mr. Decany, were available for lease for a duration of six months. Notably, this letting was subject to redemption, providing some flexibility for interested parties. The property’s unique appeal lay in its location in the town of Tramore, which has long been regarded as a desirable destination. The advertisement also mentioned that a longer term of either three lives or 31 years would be provided to any respectable tenant who demonstrated competence in managing the ventures associated with these premises. This offer was particularly attractive as it presented a pathway for individuals willing to invest a modest amount of capital in order to earn a comfortable livelihood. Moreover, the advertisement took care to emphasize the advantages of the property’s location, suggesting that it was strategically positioned to yield significant benefits to the right tenant. Prospective individuals were encouraged to draft their proposals in writing, which would be accepted by Mr. William Hill at Newtown, near Tramore, from 27 February until 2 March. This timeframe provided a brief window for interested parties to express their interest and negotiate terms.

There were three proprietors of warm water baths listed in the Tramore entry of Sherman’s Commercial Directory, 1839. Michael Cahill was the proprietor of Cahill’s Baths, which the directory informs us were formerly Dr O’Flaherty’s, a notable establishment that catered to the health-conscious patrons of the area. Interestingly, a Mrs. Flaherty was listed as the proprietor of the Strand Inn in Pigot’s Directory 1824, suggesting a connection between the baths of the time and the hospitality sector, as the inn likely provided accommodations for travellers seeking the therapeutic benefits of the baths. Additionally, a Margaret Flaherty died in Tramore in July of the same year ‘after a long and tedious illness which she bore with Christian resignation’. While the 1824 directory does not mention any bath houses in Tramore, it is entirely plausible that this Margaret Flaherty had been the owner of both the Strand Inn and the baths. The other two bath house owners in 1839 were Mary O’Neill, of the New Road Hotel, proprietor of the Middle Baths and John Browne, the proprietor of the Lower Strand Baths. The location of the Tramore baths are marked on a technical drawing from 1836. Browne’s was nearest the sea, at the entrance to the Lady’s Slip, Next door was O’Neil’s and next door to that Cahill’s.

Slater’s Royal National Commercial Directory of Ireland 1846 refers to all the bath houses in Tramore as Hot Baths, highlighting the significance of this innovation during that period. Michael Cahill, Mary O’Neill, and John Browne were still in business, but they were now joined by Mary’s son Michael, who was listed as a proprietor in his own right, indicating the involvement of the next generation in this thriving industry. The valuation books from 1850 record four bathing establishments in Tramore, specifically noted as numbers 7, 8, 9, and 11 on Strand Street, each contributing to the bustling atmosphere of the resort town. Number 7 is Cahill’s, which, with a classification of 1C+, was the oldest of the four, reflecting its long-standing presence and popularity among locals and visitors alike. O’Neil’s, recognized as the largest of the establishments, was divided into five separate houses or sections, ensuring that it could accommodate a significant number of patrons seeking relaxation and therapeutic benefits. John Browne was the owner of numbers 9 and 11, the latter of which was said to be only four years built, showcasing the growth of the bathing culture in Tramore. ‘Built all himself but the walls of the baths which were up when he took the above.’ This statement illustrates Browne’s dedication, as he undertook the construction of the premises, which consisted of a house, kitchen, baths, outhouse, coach, and stable, thereby contributing not only to the bathing tradition but also to the overall infrastructure of Tramore. The presence of such establishments in the town played a pivotal role in attracting visitors and fostering a sense of hospitality that defined the area during that era.

Mary O’Neill died on 28 November 1852, and in her will, she meticulously delineated her wishes regarding her estate, which she left to her daughters, Margaret and Sarah O’Neill. She evidently disapproved of her son Michael, as not only did she pass him over for inheritance entirely, but she also granted him £10 per annum for five years. This allowance was contingent on the stipulation that he would in ‘every way conduct himself to the satisfaction of my executors’ and that such payment ‘shall cease from the time of his misconduct’. This severe measure reflected her lack of trust in him. Unfortunately, Margaret O’Neill died tragically on 26 November 1854, just two years after her mother’s passing, which left Sarah as the sole inheritor of the family legacy. Slater’s Directory, published in 1856, lists the bathhouse proprietors in Tramore as Sarah O’Neill, Michael O’Neill, Michael Cahill, and John Browne. However, Sarah also died shortly thereafter, on 1 January 1857, leaving Michael to inherit not only the hotel but also the baths. In April 1857, Michael put the hotel up for sale by public auction, yet he may have continued in the profession of a bathkeeper. On 29 May 1857, the Waterford News reported that Captain William Fry had purchased O’Neill’s Hotel. In December 1859, Fry took steps to invigorate the business by advertising Fry’s Hotel as being open for the winter season, promoting it as a destination that offered ‘Hot and Vapour baths’ available on the premises.

It is doubtful that Michael O’Neill led a life that would have been to the satisfaction of his mother, as he died at the age of 47, of disease of the liver after an illness of six months, on Strand Street on 26 February 1868. Shortly before his death Michael agreed to have his house on Strand Street taken down to make way for the construction of a new road. Michael was a bachelor, and it appears that his bathhouses were taken over by John Browne, as it was he who was compensated to the tune of £113 for a house that was demolished in the making of the new road, which was of course Gallwey’s Hill.

Returning to Cahill’s baths, Richard Cahill inherited his father Michael’s business when he died of old age in his house on Queen’s Street on 20 January 1867. Michael was described as an 85-year-old bathkeeper. Richard married a woman named Ellen Clancy and had several children. Over the years he lived on both Strand Street and Queen’s Street and referred to himself as both a publican and shoemaker as well as a bath house proprietor.

Slater’s Directory, 1870 listed two bath house proprietors in Tramore, Richard Cahill and John Browne. However, John Browne died of apoplexy at the age of eighty, on Strand Street after an illness of three days on 23 February 1879. The informant was his sister, Catherine Browne. Slater’s Directory 1880 lists the bath house proprietors as Richard Cahill and Catherine Browne. Catherine Browne died of rheumatism gangrene at Strand Street at the age of sixty-eight, after an illness of five days on 23 July 1888. Her death certificate described her as a bath proprietress. There is a memorial headstone to the Browne family by the rear wall of the Holy Cross cemetery which reads:

‘To the memory of David Browne and his wife Catherine parents of Miss Ellen Browne Market Street Tramore, her brother John died Feb. 23rd, 1879, and her sister Catherine died July 23rd, 1888, also Ellen Browne died Nov. 20th, 1897, aged 90 years. May they rest in peace.’

Catherine left her baths to a young man named Philip Morrissey in her will. She also left £20 to Michael Phelan, a workman at the baths. Philip Morrissey’s father Edmund was the proprietor of the Railway Hotel. Philip advertised his baths on 13 July 1889, in the Tipperary Free Press:

The Great Remedy for Rheumatism and Nervousness. Ask for Browne’s warm, tepid, cold, shower and genuine reclining saltwater baths. Proprietor Phillip Morrissey. These baths have undergone a most complete renovation and further bath accommodation added. Most comfortably furnished lodgings can be obtained next to the baths and at 8 Main Street. Mr. Morrissey is also proprietor of the licensed premises 8 Main St. attached to which is a splendid bagatelle table in first class order. Best brandies, whiskies, Guinness’s XX stout, Bass’s ales can be obtained.

Probably as a result of new competition, Richard Cahill began to advertise his baths in the Waterford Chronicle on 24 August 1889 under the heading ‘Baths! Baths! Baths!’, in which he called the attention of the visitors and residents at Tramore to his saltwater baths which were then in full working order. Warm, tepid, shower or reclining could be had at any hour of the day. The baths were under the immediate supervision of the proprietor and those who patronised his old established baths could rely on the utmost satisfaction being given. He said that charges were moderate and added the address as Cahill’s Baths, opposite Railway Hotel, Tramore.

In April 1891, Philip Morrissey announced his intention to erect Turkish baths, which were to be placed under capable and efficient management to ensure a high standard of service. A journalist for the Waterford Mirror, in a June 1891 edition, reported that Mr. Morrissey’s baths were in full working order, and the Turkish baths were in the process of being erected, showcasing the establishment’s commitment to excellence. He also remarked that Mr. Cahill’s Baths were open. In October 1892, Morrissey advertised that his old established baths had undergone a complete renovation, reflecting a dedication to continual improvement, and that his Turkish baths would be opened in a few weeks amid great anticipation from the public. He proudly stated that ‘These baths will be found to be the equal to any in the kingdom, and no expense has been spared to make them a success.’ This bold claim underscored his confidence in the quality and luxury of the facilities he was offering. However, due to unforeseen circumstances, including construction delays and supply chain issues that were common at the time, the opening was delayed by several months, much to the disappointment of eager patrons who had been looking forward to experiencing the rejuvenating benefits of the baths he promised. An article in the Wexford and Kilkenny Express, 3 June 1893 entitled ‘Turkish Baths in Tramore’ read:

The enterprise of Mr Philip Morrissey, Strand Street, Tramore, is highly complimentary to that gentleman. Mr Morrissey has now nearly completed his Turkish baths, which will, when finished, be a credit and ornament to the town. The work has been carried out regardless of expense, and the various rooms are fitted up in the most improved and comfortable manner. The heating apparatus is perfect in every way, and Mr Morrissey intends shortly to erect a gas engine for the purpose of pumping up water from the bay. We need hardly point out the enormous benefit these baths will be to the residents and visitors of Tramore, and we have no doubt but that they will be largely availed of by the public. The work has been admirably carried out under the direction of Mr Morrissey, by Mr John O’Brien, assisted my Mr E Hunt, and to those tradesmen great credit is due for their careful and competent workmanship.

The Tramore Turkish Baths were eventually opened to the public on 1 July 1893. Slater’s Directory, 1894 lists Richard Cahill’s baths and Philip Morrissey’s Browne’s saltwater, shower and reclining Turkish baths. Philip Morrissey died of influenza in Main Street at the age of fifty on 21 May 1900 and Richard Cahill died of old age on 27 September 1912. There seems to have been a great respect for the provenance and tradition attached to the bath houses, as not only does Sherman’s Commercial Directory, 1839 inform us that Cahill’s baths were formerly Dr O’Flaherty’s, but Michael Cahill’s will of 1864 mentions Dr O’Flaherty’s baths forty years after the O’Flahertys owned them. While Morrissey’s baths were still partially advertised under the old name of Browne’s in The Waterford Mirror as late as 1904. The same edition held the last advertisement that I’ve come across for Cahill’s baths. There are several photographs in existence of a man drawing seawater in a barrel on his horse drawn cart and delivering it to Cahill’s baths which had an archway to allow access. Morrissey’s Turkish Bath House which was located at the right of the entrance to the Lady’s Slip also features in several photographs.

One of the last advertisements for seawater baths in Tramore that I know of was for Morrissey’s Baths in May 1909, when they were referred to as the Tramore Baths and a bath cost a shilling. The bath houses were still periodically mentioned in the newspapers up until 1919 or thereabouts, but it’s difficult to ascertain if they were still open for business. Unfortunately, with the advent of modern medicine and changing leisure preferences, the popularity of seawater bath houses in Ireland declined significantly. Many of the historic bath houses were eventually closed or repurposed for other uses, diminishing their role. Donncha Seán Ó Maidín recalled seeing the pump-house for Morrissey’s saltwater baths at the walkway down to the Lady’s Slip in the 1940s and pointed out the incline in the wall where it was located, a remnant of its former use. However, the baths had ceased to function at that time and had been replaced by holidaymakers’ chalets. Today, there are only a few remnants of these once-popular establishments of a bygone era when the therapeutic properties of seawater were highly regarded and drew crowds from far and wide.

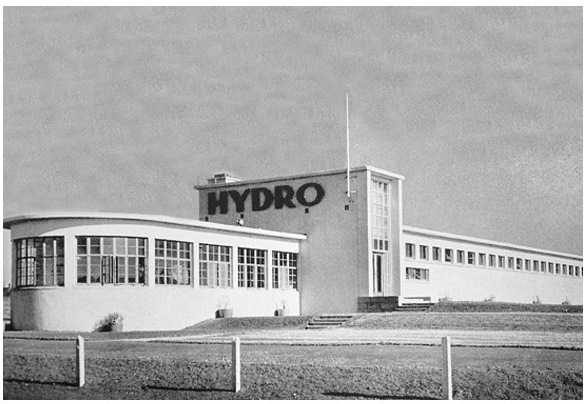

Nonetheless, the tradition of seawater bathing and its associated health benefits continued to be recognised and enjoyed at spas along the coast, fostering a unique culture around wellness that attracted both locals and tourists. Doctors would recommend salt water and salty air to cure bronchial and rheumatic ailments, believing that the natural properties of the ocean could enhance physical health and provide relief from various ailments. The Hydro was a modern spa designed by the architect Patrick Sheahan, a hospital designer known for his innovative work in health facilities, and constructed in Tramore with a grant from the tourist board aimed at promoting local tourism. It opened in 1948 with a staff of seven people, including a physiotherapist, a chiropodist, and a masseuse, all dedicated to providing a holistic approach to health and relaxation. There were several thermostatically controlled sea water baths and a restaurant, creating a full-service spa experience that highlighted the therapeutic qualities of the sea. However, it was said to be way ahead of its time, as its concept and amenities were not fully appreciated by the public, leading to financial struggles that ultimately caused it to be underutilised. Despite its intentions, the Hydro was never financially successful and lay derelict for many years before being demolished in the 1990s, marking the end of an era in Tramore’s rich history of spa culture.

Leave a comment